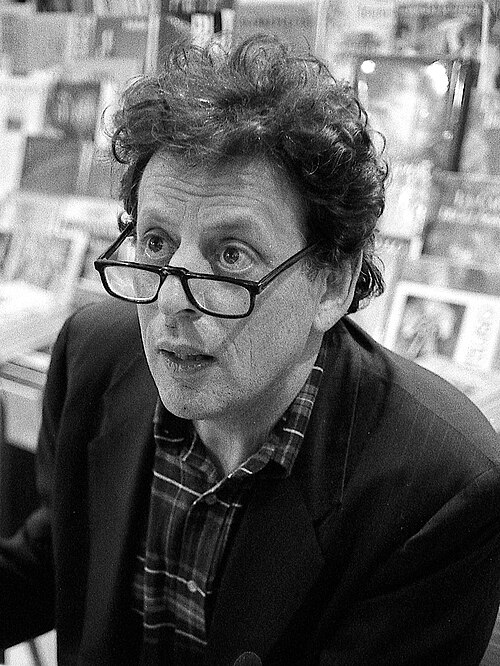

Words Without Music – Phillip Glass Part 02

This is an auto-biography, or in his own words, a memoir. Although considered one of the most influential composers of our time, the book was written with humility and ‘transparency’ (no pun intended, regarding his name).

Glass was born in Baltimore, Maryland. His parents were Jewish immigrants. His father owned a record store and his mother was a librarian. He began taking violin lessons at the age of six, and took up the flute by age twelve, studying in the Preparatory Division of Peabody.

Glass writes, “My father was self-taught, but he ended up having a very refined and rich knowledge of classical, chamber, and contemporary music. Typically he would come home and have dinner, and then sit in his armchair and listen to music until almost midnight. I caught on to this very early, and I would go and listen with him.” We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas the importance of listening to a wide range of musical styles.

At the age of 15, he entered an accelerated college program at the University of Chicago. He later studied at Juilliard with Vincent Persichetti, and attended the Aspen Music Festival.

“In the summer of 1960, four years after I had graduated from Chicago, Copland was a guest of the orchestra at the Aspen Music Festival and School, where I had come from Juilliard to take a summer course with Darius Milhaud, a wonderful composer and teacher…I had one lesson with Aaron Copland and we had a disagreement and he basically kicked me out.”

While in Chicago, Glass enjoyed listening to jazz, particularly Charlie Parker, and when he was in New York, he would frequent jazz concerts. “As a Juilliard student I would write music by day and by night hear John Coltrane at the Village Vanguard, Miles Davis and Art Blakey at the Café Bohemia, or Thelonious Monk trading sets with the young Ornette Coleman.”

According to Glass, he states that he began writing music because he wanted to know the answer to the question, “Where does music come from?” Throughout his life, he continued to ask this question of people he respected.

Among the contemporary classical composers he enjoyed and in whose music he immersed himself were Alban Berg, Harry Partch, John Cage, Conlon Nancarrow, and Morton Feldman. “In time, and much later, I came to love the music of Stockhausen, Hans Werner Henze, Luigi Nono, Luciano Berio, and even Pierre Boulez, but in 1957 I was listening to Charles Ives, Roy Harris, Aaron Copeland, Virgil Thompson, and William Schuman.”

While living in New York City, he worked various jobs to support himself. Among his various occupations were working at a steel mill, being a plumber, and a taxi-cab driver.

He knew that his musical skills were not yet what he needed them to be. “I was painfully aware of how defective my basic skills were. Whatever I had accomplished in playing the flute or piano, and especially in composition, was the result of youthful enthusiasm. In fact, I had a very poor grasp of real technique.” We want students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to know that, regardless of their background, they have great potential.

“I realized right away that I needed to quickly develop impeccable work habits….I first needed to improve my piano playing very quickly…The discipline needed for composing was a different matter altogether and required more ingenuity. My first goal was to be able to sit at a piano or desk for three hours. I thought that was a reasonable amount of time and, once accomplished, could be easily extended as needed. I picked a period of time that would work most days, ten a.m. to one in the afternoon. This allowed for my music classes and also my part-time work at Yale Trucking.”

“The exercise was this: I set a clock on the piano, put some music paper on the table nearby, and sat at the piano from ten until one. It didn’t matter whether I composed a note of music or not. The other part of the exercise was that I didn’t write music at any other time of the day or night. The strategy was to tame my muse, encouraging it to be active at the times I had set and at no other times…The first week was painful- brutal, actually…Then, slowly, things began to change. I started writing music, just to have something to do. It didn’t really matter whether it was good, bad, boring, or interesting. And eventually, it was interesting. So I had tricked myself into composing…somehow…It probably took a little less than two months to get to that place…From then on, the habit of attention became available to me, and that brought a real order to my life.” This is an important life-lesson we try to instill into the students of our music school in Odessa, Texas: diligence always wins the day!

Glass recounts that while at Juilliard, studying with Persichetti, he noticed a “division between music theory and music practice…Making the practice of music and the writing of music separate activities was poor advice. It’s a misunderstanding about the fundamental nature of music. Music, is above all, something we play, it’s not something that’s meant for study only. For me, performing music is an essential part of the experience of composing. I see now that young composers are all playing. That was certainly encouraged by my generation. We were all players. That we would become interpreters ourselves was part of our rebellion.”

Glass continued to challenge his ability to write for orchestra, “My…study of the orchestra came through a time-honored practice of the past but not much used today- copying out original scores. In my case I took the Mahler Ninth as my subject and I literally copied it out note for note on full-size orchestra paper. Mahler is famous for being a master of the details of orchestration, and though I didn’t complete the whole work, I learned a lot from the exercise.”

Glass, as stated above, came to understand the importance of the role of the performer, or the interpreter of other people’s music. “I saw that the activity of playing was itself a creative activity and I came to have a very different idea about performance and also a different idea about the function that performing can have for the composer.”

“The activity of the listener is to listen. But it’s also the activity of the composer. If you apply that to the performer, what is the performer actually doing? What is the proper attitude for the performer when he is playing? The proper attitude is this; the performer must be listening to what he’s playing. And this is far from automatic. You can be playing and not pay attention to listening. It’s only when you’re engaged with the listening while you’re playing that the music takes on the creative unfolding, the moment of creativity, which is actually every moment. That moment becomes framed, as it were, in a performance. A performance becomes a formal framing of the activity of listening, and that would be true for the player as well.” The importance of active listening cannot be overstated, and we insist that students in our music school in Odessa, Texas develop this awareness.

Glass had the opportunity, through a Fulbright scholarship, to study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. He attributes the formation of his compositional technique to her influence and training.

He travelled to Paris with JoAnne, who came from a Catholic background. They were married while being in Europe. Upon their marriage, he received a letter from his father stating, “You are not allowed to come into the hose again.” After his father had passed away, Glass went through years of counseling to try to understand why his father had stopped talking to him. His cousin, Norman, finally explained it to him.

“What happened was this. When your uncles Lou and Al got married to Gentile women, your mother wouldn’t allow them into the house anymore. So Ben (Phillip’s father) wasn’t able to see his brothers in his own home. That was a big blow to him because he was very close to them, but that was the rule and they never did come to the house again. When you got married some years later, it was your father’s chance to get even. It was as if Ben were saying that if he wasn’t allowed to see his brothers, he was going to make sure that she couldn’t see her son. When you married JoAnne, a Gentile woman, it was your father’s turn.”

Glass relates, “What made my father’s letter so incomprehensible to me, and probably why I didn’t understand it until Norman’s explanation, was that neither my father nor my mother had much interest in traditional religion. Atheism was a way of life in our family. As far as I know, my father only went to Temple twice- to see my brother and then me do the bar mitzvah rites. The fact is that the trouble in our family was not about religion. But it was the kind of dispute that sometimes happens within a family, and unfortunately it happened in mine.”

While in Paris, Glass was able to compose in theaters, which became the basis for his later work in opera, dance, and film. “The theater suddenly puts the composer in an unexpected relationship to his work. As long as you’re just writing symphonies, or quartets, you can rely on the history of music and what you know about the language of music to continue in much the same way. Once you get into the world of theater and you’re referencing all its elements- movement, image, text, and music- unexpected things can take place. The composer then finds himself unprepared- in a situation where he doesn’t know what to do. If you don’t know what to do, there’s actually a chance of doing something new. As long as you know what you’re doing, nothing much of interest is going to happen.” We hope to instill in students of our music school in Odessa, Texas the benefit of inter-artistic disciplines in collaboration.

Glass had become interested in the music of India, and while in France, he came in contact with Ravi Shankar, working on the film score of Chappaqua. Glass recounts, “The ‘problem’ occurred with the very first piece we recorded. Immediately Alla Rakha interrupted the playback, exclaiming very emphatically that the accents in the music were incorrect…I began writing out the parts again, grouping and regrouping the phrases to get the accents the way they were supposed to be heard, a very tricky business…In the midst of all this and in desperation, I simply erased all the bar lines, thinking I would just start all over again. There before my eyes I saw a stream of notes, grouped into twos and threes. I saw at once what he was trying to tell me.”

“A few moments later I saw there was a regular sixteen-beat cycle that governed the whole of the music. Later I learned…that this was called a tal and that this tal in sixteen beats was called tin tal and finally, the very first beat of the tal was called a sam (downbeat). All this is something any world music class would learn at the beginning of the first class on Indian classical music. But learning it a t such a public, high-pressure event gave it a special, unforgettable meaning. I didn’t realize at the time the effect it would have on my own music.”

Glass’ recounts that “Mademoiselle Boulanger was certainly one of the most remarkable people I had ever met…Her music studio was quite large. It had a small pipe organ and a grand piano. On Wednesday afternoon there was a class that was open to all her current students, whose presence was required. In addition, any former students who lived in Paris or happened to be there were welcome. It was customary for the room to hold up to seventy people on most Wednesdays. There would be one topic for the whole year. During the two academic years I was there, we studied all of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues, Book I, in the first year, and the twenty-seven Mozart piano concertos in the second. We were also expected to learn and be able to perform the ‘Bach prelude of the week.’ Typically the class would begin with Mlle. Boulanger calling out, without as much as looking up, the name of the one chosen to perform that morning. ‘Paul!’ ‘Charles!’ ‘Phillip!’ God help you if you weren’t prepared or, even worse, not present.”

“If someone said, ‘Mademoiselle Boulanger, I’m not a pianist,’ she would say, ‘It doesn’t matter, play it anyway.’ People who were violinists or harpists or whatever would have to sit down and demonstrate that they had learned it. If they couldn’t really play it, if the person didn’t have a piano technique, the notes would still have to be in the right place. It wouldn’t be a good performance by any means, but you were supposed to overcome the difficulties.” We expect students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to have a basic understanding of piano skills and theory.