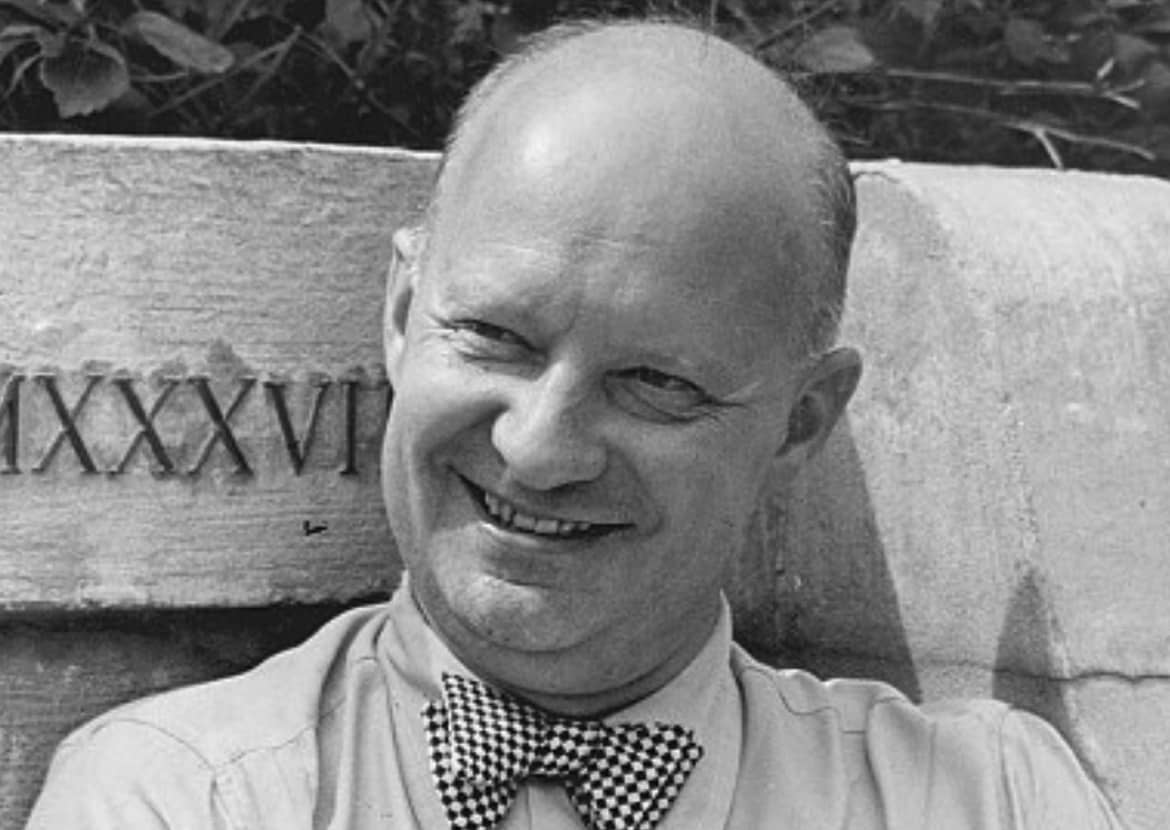

Paul Hindemith

The following contains excerpts from the book, Hindemith, Hartmann and Henze (Guy Rickards).

Although the majority of this book focused on Hindemith, its aim was to show the lineage of German composers to the present, particularly through Germany’s greatest time of demise in the first half of the 20th century.

“In purely musical terms, the Question is concerned with what happened in Germany contemporary with these events, how its dominant position in Western music was destroyed and to what extent it has recovered since.”

“Culturally, Germany has occupied a primary position in Western civilization over the past four centuries, an important element of which has been the legacy of her composers. The bedrock of Western music’s instrumental, chamber and orchestral concert repertory is provided by German composers- even if one does not count those from Austria as German- especially those of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.”

“The aim here is to provide a linked biography, set in the wider historical context, of the three German composers who collectively have been central to the development of the core tradition of German music inherited from the previous century: Paul Hindemith (1895-1963), Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1905-63) and Hans Werner Henze (b. 1926). Despite markedly different approaches and political sensibilities, all three in turn nurtured and extended this tradition by uniting the spirit of experiment with orthodox German expression.” We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to study these German composers..

“German music in the latter half of the nineteenth century had been divided into two camps, each centered on a particular figurehead composer. One, surrounding Johannes Brahms, extolled a classical viewpoint with Brahms as the direct and natural heir of the Viennese Classical masters- Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven. The opposed camp were Romantics by orientation and grouped about the outsize persona of Richard Wagner, whose music had probably pushed back the boundaries of music further than anyone. The composers of the Classical Period, extending roughly form the death of Johann Sebastian Bach in 1750, to that of Beethoven in 1827, had maintained a common language in composition that took little account of ethnic and political boundaries. But the rise of the Romantic Movement in art and literature inevitably caught music in its wake and engendered the development of a more personal voice in composition…The division between classicizing and romantic forces continued in German music into the twentieth century.”

“German musicians and composers were at the forefront of new music during the years of the Weimar Republic (1920-33) between the two World Wars and in the Federal Republic after 1945. Hindemith in particular was associated with this pioneering spirit during the 1920s, as was Henze in the late 1940s and 1950s. In between these periods of rampant experimentation occurred nightmare of oppression when all such adventure was stopped dead in its tracks by the political ideologues of the Nazi party. Germany between 1933 and 1945 was denuded of most of its wealth of artistic and scientific talent by the racist policies of the Third Reich.”

“An essential part of the post-war revivification of German musical culture was the aggressively radical movement, led by Karlheinz Stockhausen and his French colleague, Pierre Boulez, centered on the annual composers’ summer school at Darmstadt.” We teach the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas about these composers.

“Paul Hindemith was of humble origins, unlike most composers at this time who were drawn from the middle and upper echelons of society.”

He grew up in a musical family, and began playing violin and viola with his family. He studied at the Hoch Conservatory, which was founded in 1878 by Franz Liszt. “Hindemith made his debut as a composer when a fellow student performed a short set of Variations in E flat minor on an unknown theme for the piano (1913).”

“Hindemith’s debut as a conductor was given at a Hoch Conservatory concert on 28 June 1916.”

“One of his most uncompromising works was the virtuoso’s Second sonata for Unaccompanied Viola, the first item of the opus 25 set. The fourth of its five movements, an astonishingly wild study in perpetual motion, was reputedly written in the buffet car of the train carrying Hindemith on his way to its first performance.”

Hindemith had become an exceptional violinist and violist. He held the position of concertmaster of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra, and later formed and toured extensively, playing viola in the Amar String Quartet.

He was interested in the emerging jazz movement in the early 20th century as well as the burgeoning motion picture industry. “Hindemith experimented with synchronization of music with pictures, producing two film scores: Felix the Cat at the Circus, using a mechanical organ, in 1927 and Vormittagspuk (‘Haunting in the Morning’), which used the pianola, a year later. Thereafter, Hindemith concentrated on purely acoustic instruments although he remained fascinated by exotic ones. Examples can be found in the Trio for Viola, Heckelphone and Piano of 1928 and the Konzertstuck composed in 1931 for an early electronic instrument, the trautonium.”

“In February 1927 Hindemith was appointed professor of composition to postgraduates at the Hochschule for Musik in Berlin.”

Even during the ramping up of Nazi Germany, Hindemith was reticent to leave. “As with many Germans who were not politically active, Hindemith may have misjudged the Nazis to be a temporary phenomenon. The Jewish composer Berthold Goldschmidt recalls that Hindemith advised him to stay put- ‘They are idiots, they won’t last.”

Hindemith, however, became a target of the Nazi leadership, due to his aggressively experimental creativity at the time. “The ban on his music was never officially proclaimed, but this did not prevent the press, under Goebbels’ instigation, from mounting a vitriolic onslaught against Hindemith. In November 1934, Hindemith threatened emigration if the attacks did not stop.”

“Hindemith began to realize that he was not going to be reconciled with the government of his country. In March 1937, following his third trip to Turkey, he resigned from the Berlin Hochschule. He sailed alone to North America for a short concert tour…In September 1938, Hindemith finally left Germany and moved to Blusch, a picturesque village in Switzerland.”

In 1940, Paul and Gertrud (his wife) left for the United States. “At the end of April 1940, following some lectures, he was offered a post as visiting professor of music theory at Yale University to commence in September. Through the summer Hindemith ran a workshop at Koussevitsky’s instigation at the Berkshire Music Festival summer school at Tanglewood. Three of his students there went on to achieve international prominence as composers in their own right: the young German émigré, Lukas Foss, Harold Shapero, and, best known of all, Leonard Bernstein.” These are also worthy composers to study, and we encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to become acquainted with their excellent work.

At the time, he was working on a ballet, The Four Temperaments (exploring the melancholic-sanguine-phlegmatic-choleric, each with its own separate movement) with the choreographer George Balanchine.

He also composed the ballet Herodiade for the great American choreographer Martha Graham, October 30, 1944.

Hindemith wrote several books, detailing theory, composition and music philosophy, primarily for the courses he taught at universities: Elementary Training for Musicians (1946), A Concentrated Course in Traditional Harmony, Book 1(1968), A Concentrated Course in Traditional Harmony, Book 2 – Exercises for Advanced Students (1964); The Craft of Musical Composition: Book 1 – Theoretical Part (1942); The Craft of Musical Composition: Book 2 – Exercises in Two-Part Writing (1941); The Craft of Musical Composition: Book 3 – Exercises in Three-Part Writing (1970, published posthumously) We derive some of the teaching in our music school in Odessa, Texas from these resources.

Hindemith’s final book, A Composer’s World, published in 1952, was derived from a series of six lectures given in late 1949 at Harvard University.

Hindemith visited Stockhausen’s electronic studio in Cologne, but his interchange was less than enthusiastic. Stockhausen said, “I was…disappointed that this man simply denied my musicality.”

Perhaps Die Harmonie der Welt , Hindemith’s opera, can be seen as his magnum opus, “into which he poured his lifetime’s experience and theoretical consideration. The failure of its premiere in 1957, which he conducted, was a great disappointment to him.”

“The role of German music in the twentieth century cannot be overestimated. It has been a tale of domination and retreat, experiment and control, research and systematization that has mirrored the political and military fortunes that the nation has endured. There is probably no area of Western music that has not been touched by the Expressionist and atonal movements that arose around the time of the First World War or serialism after the Second.” We teach serialism concepts to the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas.

“Hindemith, Hartmann and Henze were all involved with radicalism in both the musical and political arenas. All three indulged in experiments early in their careers and helped to foster the continued development of new music by others. In the event, all of them moved away from a pioneer stance, tending to avoid the dictates of schools or cliques. Ultimately, their musical roots are intertwined and spring from the mainstream tradition of Germanic music. There is an audible progression from the music of Bruchner, Reger and Richard Strauss through Hindemith’s, Harmann’s and Henze’s works. In the second half of the twentieth century this tradition became sidelined by the more media-conscious experimenters who adhered to an alternative progression from the music of Mahler and the new Viennese school of, principally, Schoenberg and Webern. Henze and, to a lesser degree, Hartmann, were both flexible enough to take advantage of both areas of activity; Hindemith remained more conservatively faithful to the old ways with a backward-looking but still vital method. Hartmann and Henze both learned much from Hindemith’s music, particularly that of the 1920s. Hindemith and Hartmann both exercised a direct influence on Henze.”

“At various times in their careers Hindemith, Hartmann and Henze were not permitted the luxury of thinking differently in Germany, yet still managed to pursue their artistic vision by recourse to exile, either internal or external.”

“The individual legacies of these three composers are, however, highly varied. Hindemith will be remembered chiefly for the opera Mathis der Maler and the symphony culled from it, along with a handful of genuinely popular orchestral works, such as the Symphonic Metamorphoses on the Themes of Weber and several solo concertos…his crucial work as a teacher and theorist should not be underestimated and was international in scope.” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to study Hindemith’s work deeply.

“When Hindemith died in 1963, his life’s work was substantively complete. Hartmann died too young and this loss must be counted amongst the greatest in modern peacetime Germany. Henze as a composer is still developing new ideas although the music of his seventh decade bears signs of greater stylistic unity.”

“Hindemith was perhaps the instrumental composer par excellence: a virtuoso on both the violin and viola as well as technically of concert rank on the piano and clarinet. He possessed an innate practical musicality that allowed him to acquire a working knowledge of almost every standard (and several definitely non-standard) instruments, something he tended to demand, unreasonably or not, from his composition students. He was a man who seemed to live and breathe music and his ever-inquisitive mind led him to examine and write for many unusual and exotic species.”

“Hindemith, by entering the standard repertoire, rooted in the Classical and Romantic periods with a few truly popular works, has attained a status analogous to those twentieth-century composers like Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Stravinsky, who have found a different audience neither concerned by, nor versed in, the conventions of art music. If Mathis der Maler cannot be compared in terms of public appeal to Peter and the Wolf or the Rite of Spring, it has none the less become a staple of the modern orchestral repertoire. Neither Hartmann nor Henze has enjoyed such success, but Henze’s stature amongst the smaller and more informed audience of contemporary music is by far the greatest of the three. Hartmann in many respects falls between the two, neither as traditionally based nor as popular in appeal as Hindemith (the music is perhaps too aggressive for that) not as consciously revolutionary and innovative in intent as Henze.”

I have great admiration for Hindemith’s work and am growing more aware of Hartmann and Henze. Hindemith was not politically active or religious, although his wife was a devout Lutheran, while Hartmann and Henze were secularist. Henze leaning politically left, is an avowed Marxist and homosexual.

The historic musical progression from that of J.S. Bach to the contemporary Classical Music of today is still structurally similar, which amazes me. While the distance the art has travelled is long, there are still similarities that can be clearly seen.