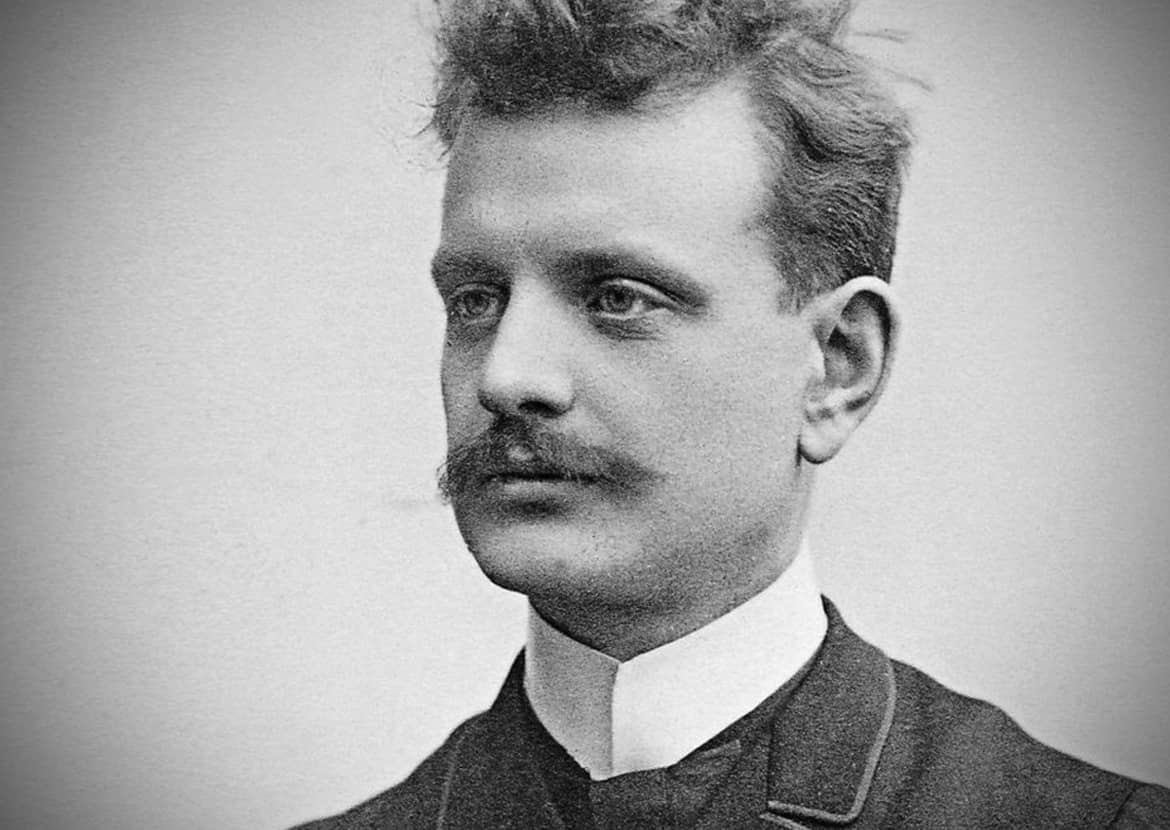

Jean Sibelius

The following contains excepts from the book, Jean Sibelius (Guy Rickards).

This was a very well-written and scholarly book detailing Sibelius’ life and musical output, showing the composer’s struggles and triumphs in the midst of a volatile world. He lived in Europe through two world wars, and struggled to make ends meet financially, to support his wife and children. Although he had a few successes in his artistic output, he often times was forced to create works that were less than high achievements, simply to make a living. We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to find ways to make their artistic projects relevant to their culture.

He is considered to have been a strong voice in the Romantic/Modern eras of Western Classical music, a nationalist of Finland, and a herald of a new style or genre of music that uniquely combined Classical technique with Nordic folk music. Perhaps his most famous work is Finlandia, which became his nation’s national anthem, and is still played today at the Olympic Games.

“More than any other single factor, the music of Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) is quintessentially the product of the natural landscapes) physical, ethnic, historical and political) of his native country…climate of short, hot summers and long, cold winters.”

“His father, Christian Gustaf, was the town doctor…His wife, Maria Charlotta, was a preacher’s daughter of a more restrained, even austere, disposition.”

“Evidence of Janne’s musicality emerged only gradually through his childhood. His gift of perfect pitch…” We teach pitch memory to the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas.

He began learning the violin at age 15 and made quick progress. His family moved to Helsinki in 1885, where he enrolled in the music at the University, where he studied violin and began writing music. While there, he met Aino Jarnefelt, who would later become his wife.

Sibelius moved to Berlin to further his studies, where he came in contact with the pre-eminent violin virtuoso (and colleague of Brahms), Joseph Joachim. Although Sibelius still studied violin, his predisposition toward composition led him to spend more of his time writing.

He then spent time in Vienna, again furthering his studies with Karl Goldmark and Robert Fuchs, where he wrote Kullervo, a symphony on the largest scale, a piece lasting 70 minutes, the largest composition he is known to have written. Kullervo propelled him to national prominence as a spokesman for Finnish culture.

“After his return to Finland in August, Sibelius came into contact with Axel Carpelan, the formerly anonymous fan who had suggested the idea of a piece called Finlandia. Carpelan was full of good ideas and suggestions: Sibelius should write a violin concerto, another symphony, music to Shakespeare; Sibelius should visit Italy for inspiration. It is a measure of what Carpelan came to mean to Sibelius that all of these suggestions, and many others, would in the fullness of time be acted on. Indeed, over the next nineteen years until his death Carpelan became as indispensable to the composer as he was indefatigable in his support, particularly in the crucial role of unpaid and self-appointed fund-raiser. Carpelan himself had no wealth, but his connections in moneyed circles enabled him to secure enough financial support for Sibelius to start devoting himself to composition.”

The Violin Concerto, one of Sibelius’ most beautiful works, was written in 1904, to be premiered by Willy Burmester in Berlin. “The Violin Concerto’s first performance did not go well…In several places soloist and orchestra came unstuck, so that a clear view of the piece was hard to obtain…Sibelius withdrew the work for revision…(excising around ten percent of its original length…), as well as lightening the orchestral textures to achieve a brighter sound. The final version was launched by Karl Halir in Berlin under Richard Strauss’s direction in October 1905…The great Joachim, present in the audience for the revision’s first performance, echoed Flodin’s opinion of the original: ‘terrible and boring’. The concerto, with its ‘jolly, tearing finale’ (to quote Ralph Wood), the main theme of which was described by Sir Donald Tovey as ‘evidently a polonaise for polar bears’, only set public enthusiasm alight in the 1930s through the sustained advocacy of the leading virtuoso of the day, Jascha Heifetz. Thanks to his commitment, and a brilliant recording made in 1935, the work went on to become one of the standards of the modern violin repertoire.” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to study this beautiful and preeminent work.

Sibelius’ 3rd Symphony, “the first of the truly great Sibelius symphonies- has been generally misunderstood and did not succeed with audiences or the bulk of critics to anything like the degree of the First of Second. So complete was the incomprehension that greeted the work that its lack of success was at least partly attributed by many to the composer’s use of Finnish folk elements, whereas in fact this was intentionally the most cosmopolitan and international score Sibelius had yet attempted to compose.”

The composer wrote Carpelan, which gives insight into his creative mindset:

“You mention interconnections between themes and other such matters, all of which are quite subconscious on my part. Only afterwards can one discern this or that relationship but for the most part one is merely the vessel. That miraculous logic (let us call it God) which governs a work of art, that is the important thing.”

“The Fourth pushed the symphony as a genre, and the use within it of tonality, to the most extreme point possible- one critic called the work ‘the most modern of the modern’ – though without busting over into the atonality, the total absence of key, that was the basis of the music of Arnold Schoenberg…When Paul Weingartner tried to perform the symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1912, the musicians simply refused to play it- and it has still not been performed there.” Although, at times, composers stretch for creativity beyond that of their audience’s ability to appreciate, their artistic achievement is nonetheless critically important. We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to be pioneering in their attitude.

“If posterity has tended to value the creations of the ‘abstract thinker’ side of Sibelius rather more highly than the ‘notesmith’, the latter aspect formed as vital a part of his make-up. It was the ‘notesmith’ side that was able to keep on producing saleable pieces when the ‘thinker’, at the mercy of the caprices of inspiration, stayed silent.”

Sibelius, at times had financial struggles, as he once wrote:

“My domestic harmony and peace are at an end because I cannot earn sufficient income to supply all that is needed. A constant battle with tears and misery at home. A hell! I feel completely unworthy in my own home…Poor Aino! It can hardly be easy to manage the house on so little. It makes me more than aware of the truth in the old saying: do not marry if you cannot provide for your wife in the style to which she was accustomed before. The same food, clothes, servants- in a word the same income.”

Touring the United States in 1913, he was treated, however, as a celebrity, and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Yale. “He was the guest of honour at numerous functions, meeting a host of American composers and other worthies- the most eminent being former President Taft…There were plans for him to return to North America the following year for a concert tour, and Sibelius believed that he might then be able to wipe out his debts at one fell swoop. But while he was at sea something happened in the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo, which dashed all his hopes and plans…Five weeks later, World War I began.”

“Few composers have come to be seen, in the fullness of time, as the very embodiment of their country…Sibelius’ music remained misunderstood in Germany…Otto Klempere’s judgement, however, was rather that his ‘achievement was to create an altogether new music with completely classical means.’” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to be aware of, and relevant to their culture.

“Taken as a whole, the extreme variability in quality of Sibelius’s music has caused many commentators, even avowedly well-disposed ones such as Robert Layton, to question his final standing amongst acknowledged ‘greats’ such as Beethoven, Brahms and Mozart…And however sublime the very best of Sibelius’s music is, the embarrassing emptiness of a large section of his output is often held to have diluted the value of the whole of it…as were Mahler and Shostakovich in very different ways, this was not due to the nature of his gifts but because of harsh financial imperatives and personal- but non-musical- weakness. He himself drew a distinct line between his bread-and-butter writing, over which his hyper-criticality was rarely exercised, and the symphonies and tone-poems that were his mission in life. And whether the critical fraternity likes it or not, it has very often been the smaller works, like Finlandia, Vase triste or the Karelia Suite, that have won Sibelius an immovable place in the affections of music-lovers at large.”

“Was Sibelius then a ‘great’ composer, or merely one who could at times achieve great things? This was a question he was all too conscious of, and the burden of his own- and what he perceived as others’ – expectations of what constituted great music finally cause his creative instincts to seize up irreconcilably. What he produced in the meantime counts at its finest amongst the pinnacles of Western music of this or any other century. If his legacy has not until now been fully explored and developed, the blame can hardly be laid at his door. His music survived the vicissitudes of fashion across a century and has still been found to contain within it seeds for the future, especially with regard to the organic development of themes. These would seem the classic hallmarks of a great composer.” We teach the students in our music school to be true to their artistic vision, as well as being relevant to their culture.

Perhaps one of the reasons I went in the direction of a musical career was a recording my parents used to play in our house, as I was growing up: Jascha Heifetz playing the Sibelius Violin Concerto. I simply fell in love with the piece and the recording. I have always admired his music and felt a kindred spirit in his creative ‘bent’. His music has elements that are mysteriously separate and distinct from the main direction of Western art music. It seems, somehow, more Eastern, more intuitive.