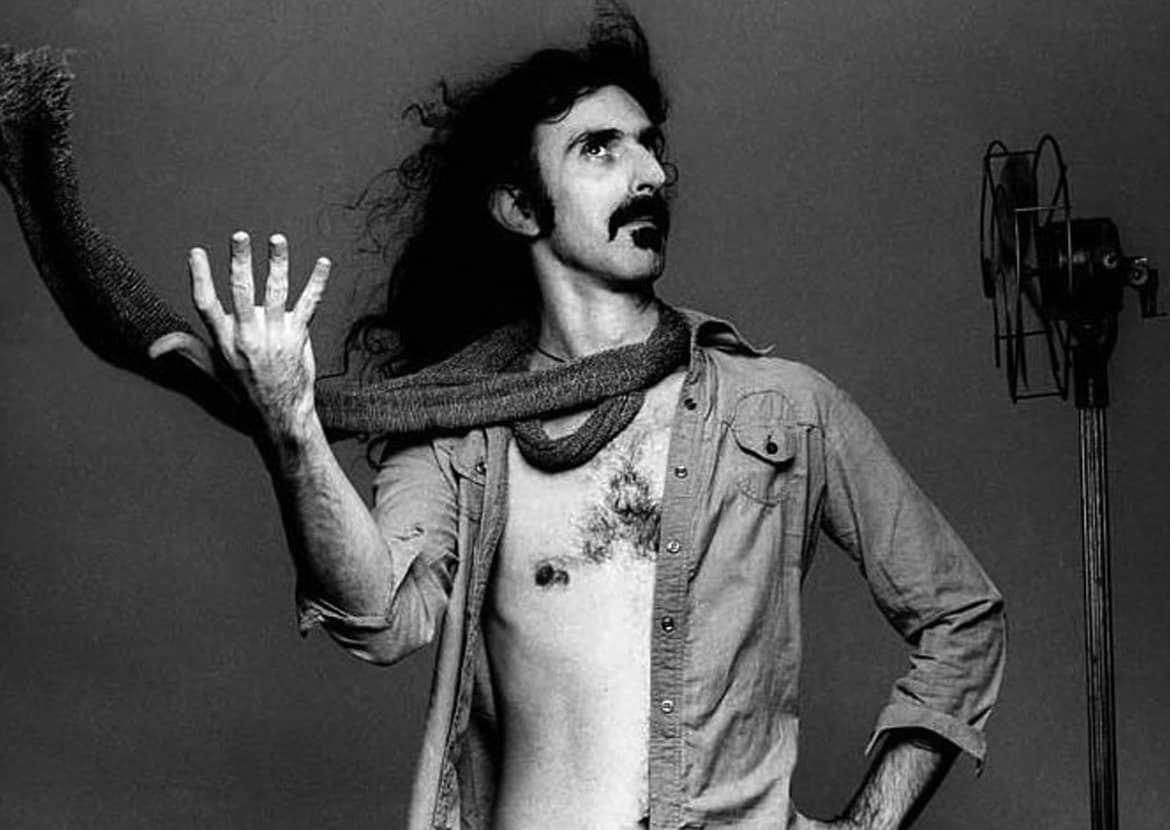

Frank Zappa

The following contains excepts from the book, Frank Zappa (Neil Slaven).

Frank Zappa was not in any way a role-model for Christian virtues. There are, however, several characteristics about his life that are admirable, such as his willingness to boldly create without regard to ridicule or cultural ambivalence, or his ability to imbed humor into his musical creations, or his stiff personal work-ethic and drive towards excellence, along with his own uncompromising pursuit of personal growth as a musician. He was, essentially, a Rock artist with highly developed Classical disciplines, which set him apart from the rest of the Rock world at the time, and has propelled his work into history, while other artists from his era have lost historic relevance. Although the main tenor of his life and work are set in a framework of pessimism and cultural anarchy, he did have the ‘gift’ to provoke questions in the American culture that were probably important to ask.

He was born December 21, 1940 in Baltimore, Maryland to a family struggling to make ends-meet, with a scientist father (meteorologist), who would have to move frequently, uprooting the sizeable family. “Frank was bright and easily bored, at home and at school, by subjects that didn’t interest him.” He was, however, interested in music. By his own admission, “I was a massive Spike Jones fan…and when I was six or seven years old, he had a hit record called ‘All I Want For Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth’ and I sent him a fan letter because of that…I used to really love to listen to all those records. It always seemed to me that if you could get a laugh out of something, that was good, and if you could make life more colourful than it actually was, that was good.”

“It was his interest in art that led Frank to become intrigued by musical notation. “I liked the way music looked on paper…It was fascinating to me that you could see the notes and somebody who knew what they were doing would look at them and music would come out. I thought it was a miracle.”

As a teen, he became interested in one of Classical music’s most pre-eminent contemporary composers, Edgard Varese, who had written ‘Ionization’ in 1931, in Paris. Frank wrote Varese a letter hoping to meet him while he was travelling in America, in which Varese responded: “Dear Mr. Zappa, I am sorry not to be able to grant you your request. I am leaving for Europe next week and will be gone until next spring. I am hoping however to see you on my return. With best wishes, Sincerely, Edgard Varese.” The meeting never took place, however. Varese died on November 6, 1965. Frank later framed the letter and hung it in the workroom of his Laurel Canyon home. We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to reach out to successful artists.

Frank was also interested in the work of Moravian composer Aloys Haba, one of the first to experiment with quarter tone intervals, and among Pop genres, he Frank was drawn to R&B artists. As a teenager, Frank formed his own R&B band, called the Blackouts. Eventually, Frank payed $300 for his own concert, featuring his own music in 1962 at Mount St. Mary’s College. He said, “It was all oddball, textured weirdo stuff…I was doing tape editing of electronic music and part of all the pieces had this little cheesoid Wollensack tape recorder in the background pumping out through mono speakers.”

After he was out of school and had formed friendships with a number of other musicians, he formed a band which was eventually called the “Mothers of Invention” featuring Frank’s own music. He felt, at this time, that he had identified a niche in the marketplace for a form of music of his own devising. “I composed a composite, gap-filling product to plug most of the gaps between so-called serious music and so-called popular music.” We encourage bold creativity in the students of our music school in Odessa, Texas.

“Despite his plans and projects, Frank was starving. If his band had a reputation it was for being unemployable and, through that, it was hard to keep as stable personnel…Frank continued to write songs, most of which turned up on the Mothers’ first three albums. Increasingly, they reflected his antipathy towards both his peers and the authorities opposed to them.”

Eventually, through some relationships in the ‘Freak’ genre community, a manager from MGM, took notice of the band. “Tom Wilson was a Harvard graduate with a degree in economics. As a producer at Columbia, he made Simon and Garfunkel’s first album, Wednesday Morning…as well as Bob Dylan’s Another Side of Bob Dylan.”

“Wilson appreciated Frank’s evident talent and regretted the inadequate means of portraying it: ‘Zappa’s a painstaking craftsman, and in some ways it’s a pity that the art of recording is not developed to the extent where you can really hear completely all the things he’s doing because sometimes one guitar part is buried and he might have three different-sounding guitars overdubbed, all playing the same thing.”

He’s always ahead of his time, however. A reviewer from the San Francisca Chronicle wrote of one of Frank’s concerts, “The Mothers…are Hollywood hippies full of contrivance, tricks and packaging; a king of Sunset Boulevard version of the Fugs. They are really indoor Muscle Beach habitués whose idea of a hip lyric is to mention ‘LSD’ or ‘pot’ three times in eight bars.” And another reviewer wrote, “With voices that should put an alley cat on a fence at midnight to shame, these ‘mothers’ have wasted two records and an album cover of indescribably poor taste recording 80 minutes of pure trash.” “Writing in the December issue of Queen, Nik Cohn dismissed the Mothers’ music as ‘revamped Dad, souped-up Ginsberg and warmed-over Dylan. The only thing new about the Mothers is the speed and glibness with which they’ve become successful…plain dull. This record is meant to be a brain-storm, a wild fit, and it should be monstrous of lovely, obscene or apocalyptic. Instead, it sounds tentative and self-conscious, painfully aware of how naughty it’s being.”

While being signed to MGM/Verve, Frank became known for his skill at arranging, and actually wrote ‘Lumpy Gravy’ (a half-hour oratorio that combined the elements of rock band and orchestra) in about 11 days. He became known as “the most avant-garde arranger in rock’n’roll.” We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas how to arrange for orchestra and rock.

Frank had unique ideas of how music could be formed, “The spoken word is differentiated from the sung word, in its rhythmic sense, as in poetry. But even normal speech patterns are beautiful in themselves…what they’re saying is useless; but if you listen to it as a piece of music…I like to simulate things like that.”

Frank’s band began touring world-wide, and in a European tour, he had good success, however, he “was unnerved by the attitude of those he had met and been interviewed by, many of whom regarded him with something approaching messianic fervor. He was expected to behave like a leader of youth opinion and instruct his followers on how to overthrow the system, whatever the system was. It was the same undirected revolutionary urge that he’d dissociated himself from in America. But while he like to provoke and declaim from the stage, Zappa had no pretensions to real power. He may have believed the polemics he delivered but his audiences failed to realize it was part of the show, just as his songs were but one aspect of his musical output.”

In America, Zappa, now gaining more favor, a Los Angeles Times reviewer wrote, “Zappa is a brilliant musician with a flair for satire…Unfortunately, he tends to do things a couple of years before people are ready for them and often crowds so many ideas into such brief musical space that they get lost in the confusion…The record is largely a series of polemics but Zappa’s barbs are witty enough to make his messages entertaining. Zappa is pop music’s bravest iconoclast and perhaps its brightest.”

Frank worked his musicians hard to produce quality products and shows. Discontent within the band was voiced by one of its members, “The band at that time was very much like the Lawrence Welk of rock’n roll. Frank wrote all the charts. Everything was very prescribed. There was no room at all for any emotion…Frank would write piece after piece and they would all have to play it exact… they became more alienated by the fact that he would overwork and became totally inhuman.”

Frank, however, did have some leadership skills, finding how to include the strengths of certain musicians in his arranging. One member wrote, “He really knew what buttons to push, emotionally and musically. He was a remarkable referee. He knew how to synthesize people’s personalities and talents. That’s a very rare gift. He wasn’t just a conductor standing there waving his arms; he was playing us as people! I became a perfectionist, I suppose because I had to be.” We encourage students in our music school to understand the value of working with people in collaboration. This takes a certain degree of leadership and people skills.

One of his keyboard players, George Duke told Keyboard magazine, “If you didn’t get it, Frank would know it. He would look around at you and make you do it again. On stage! He would make us go over one lick until there was no way we could forget it. That was some of the most difficult music I’ve ever played, partly because he composed a lot of it from the guitar. Frank’s music was like organizes chaos. That’s exactly what it was.”

“For all his compulsion to write music, Frank still fought shy of being regarded as a composer. ‘I don’t think a composer has any function in society at all…especially in an industrial society, unless it is to write movie scores, advertising jingles, or stuff that is consumed by industry. If you walk down the street and ask anybody if a composer is of any use to any society, what kind of answer do you think you would get? I mean, nobody gives a ***…If you decide to become a composer, you seriously run the risk of becoming less than a human being. Who the *** needs you?”

Being a perfectionist in the recording studio, someone asked whether he would ever use a producer again. He replied, “I would if I thought I could find somebody who would produce things the way I want to hear them. But the details that I worry about when I go into a studio are how the board is laid out, what EQ is going to be on the stuff you’re listening to in the headphones, what kind of echo you’re going to be using, how long you should be taking to do such-and-such, because at $150 an hour you don’t’ want to be wasting your time in there.”

In a conversation with Nigel Leigh, he related, “I like to find players that have unique abilities that haven’t been challenged on other types of music…I could always make do. You can’t always get what you want, so a lot of times I would be such with musicians that were merely competent. I would try and push the envelope and teach them new techniques and see whether they could adapt and grow into another style. But for me, it was always more interesting to encounter a musician who had a unique ability, find a way to showcase that and build that unusual skill into the composition. So that forever afterward, that composition would be stamped with the personality of the person who was there when the composition was created.” Learning how to work with the people you have is central to success. We teach the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas the value of working with others.

He was not always happy with the kind of musician he had to work with. “I’ll tell you, the kind of musician I need for the bands that I have doesn’t exist…I need somebody who understands polyrhythms, has good enough execution on the instrument to play all kinds of styles, understands staging, understands rhythm and blues, and understands how a lot of different compositional techniques function. The main thing a person has to have is very fast pattern recognition and information storage capability. That’s because we play like a two, two-and –a-half-hour show not-stop with everything organized…So it requires a lot of memorization- sat memorization. You can’t spend a year teaching somebody a show.”

“When Frank was there at the rehearsal and inspired, he would write with the band the way someone else might write at the piano, or with a piece of score paper, or at a computer. It was really amazing how quickly he could get stuff together, and get really good players to interpret it and make it sound like Frank Zappa music. Frank’s just about the only guy who did not compromise his music at all, and still make a living at it.”

From another band member, “He rehearsed us to death…I’ve never rehearsed that way in my life, before or since. First, he would lay all this music on you, which was a conglomerate of styles: ‘Fifties rock ‘n’roll, punk rock, new wave, jazz, Bela Bartok, Greek folk music, and weird 12-tone stuff. You had to put on all these different hats, and be quick and spontaneous about it.”

From Tommy Mars, “Frank loved to test the band members…I’ll never forget one tour. We were getting ready to go to England. Then, three days before we went out, Frank cane to rehearsal and said, ‘I want every piece in this show to be done reggae. I don’t’ care if we stay here until the tour starts, that’s what we’re gonna do…He was extremely difficult sometimes. He knew exactly what button to push. I saw people who revered him so much, who were very dropsy but who didn’t have exactly what he needed, absolutely cremated on the spot by him, in rehearsal, in auditions, politically, comedically, and tragically. He couldn’t be happy until it was ready to break.”

From Frank’s own perspective, “Well, I’m a hard taskmaster all the time…For whatever I do. I don’t have any control over the way they perceive me but this is a situation where they get a pay check and they either do the job or they don’t’ do the job. I don’t’ hire them to be my buddies.” In another interview, he admitted, “I’m the worst person you could work for and the best. Yes, there is tyranny and personal abuse. It produces the desired effect.”

When rebuilding his band because he wasn’t satisfied, he said, “I think I’m probably gonna start auditioning again…because I haven’t yet found a keyboard player who is ‘roadable’ and who can really read music…I’m talking about someone who can look at the most difficulty stuff on a page and the notes come flying off, that means less time and trouble teaching the stuff to the rest of the band. Then he would have to re roadable. By that, I mean have the flexibility to go from playing simple backgrounds to really difficult written-out stuff, plus have the attitude so that he would enjoy touring. I haven’t had too much luck finding someone who can do all those things because he probably doesn’t exist.”

He said that he was finding it difficult to find a player that understood texture. “Well, see, music is based on contrasts, contrasts between things that are very simple and things that are very complicated…This is a problem I face as a composer and an orchestrator; musicians always look at it like anyone who tells them what to play is inhibiting their lifestyle. Once the musicians learn the songs in rehearsal, once they learn the arrangements and we get out on the road, the songs sound good. But as soon as the lights go on and the audience claps a few times, everybody starts adding their own little things. By the end of the tour, a lot of things sounds like chaos. This is one of the reasons why some people lose their jobs.”

His critique of the American audience was that Americans hated music but loved entertainment. “The reason they hate music is that they’ve never stopped to listen to what the musical content is because they’re so befuddled by the packaging and merchandising that surround the musical material they’ve been induced to buy. There’s so much peripheral stuff that helped them make their analysis of what the music is…The way in which the material is presented is equally important as what’s on the record.”

Amazingly, Frank Zappa became one of contemporary Classical music’s most lauded composers through a relationship that was formed with the St. Petersburg born pianist and conductor, Nicholas Slonimsky, who introduced him to perhaps the most well-respected name in the contemporary Classical world, composer/conductor Pierre Boulez. We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to be eclectic in their musical journey.

Frank wrote a number of orchestral projects, such as ‘Sinister Footwear’ to be premiered “in the spring of 1984 with the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra and the Oakland Ballet Company. ‘The Perfect Stranger’ was a commission from Pierre Boulez, to be premiered in Paris on January 9, 1984, with his Ensemble InterContemporain.

Conductor Kent Nagano, of the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra stated, “I looked at them (the scores) and realized they were far too complicated for me to comprehend just sitting there…These kinds of musical syntaxes usually take a master’s degree to even grapple with, and even then, most composers with degrees don’t’ necessarily have the inspiration to go along with their knowledge…From my knowledge of his music and his incredible musicianship, I knew that for him it was just as important to have music performed as close to perfection as possible as it was me.”

Nagano compared what Frank was doing to the work of Pierre Boulez, but Frank didn’t agree. “Boulez writes complex rhythms, but they are mathematically derived, while the rhythms I have are derived form speech patterns…they should have the same sore of flow that a conversation would have, but when you notate that in terms of rhythmic values, sometimes it looks extremely terrifying on paper.” According to Zappa, his orchestral works contained a “purely original system for balancing the tension zones and relating zones.”

Although Frank loved working with a live orchestra, he was frustrated with the lack of detail he could get from such short rehearsal time, due to the cost of hiring that many musicians. He once wrote, The orchestra is the ultimate instrument and conducting one is an unbelievable sensation…from the podium (if the orchestra is playing well), the music sounds so good that if you listen to it, you’ll ***up. When I’m conducting, I have to force myself not to listen, and thing about what I’m doing with my hand and where the cues go.”

Early versions of what is now ‘sequencing’ with a computer DAW (digital audio workstation) was just becoming available in an instrument called the Synclavier, which Zappa took to immediately. “You see, once you learn how to do this stuff, it’s dangerously addictive. If you love music, and you desire the ability to write down you music and then push a button and hear it played back to you right away- the Synclavier is the instrument for you…It expedites everything. All the different mechanical aspects of putting a piece together- it’s like a musical word processor that would read to you. Like if you were writing a novel, for example, on a computer and the word processor helps you to move your paragraphs around and do all that stuff.”

He goes on, “Every composer has some image in his mind of what he wants his stuff to sound like, not just the composition, but the overall tonal quality of what he’s writing. In my head I have an audio image, not just of the notes, but of the way the notes will sound played in an idealized airs space, which is something you can’t get in the real world. The closest you can get to it is a digital recording with digital control over imaginary audio ambience. The moment you get your hands on a piece of equipment like this, where you can modify known instruments in ways that human beings just never do, such as add notes to the top and bottom of the range, or allow a piano to perform pitch-bends or vibrato, even basic things like that will cause you to rethink the existing musical universe. The other thing you get to do is invent sounds from scratch. Of course, that opens up a wide range.”

This kind of control was appealing to Zappa. And even though he had embraced the Symphonic Orchestra, while under the direction of the most respected leadership of Pierre Boulez, he could still not be happy enough.

“Once again, Frank was not satisfied with their live performance. He though the Ensemble under-rehearsed and he was most unwilling to take the bow that Boulez forced upon him. “I was sitting on a chair off to the side of the stage during the concert and I could see the sweat squirting out of the musicians’ foreheads.” He went on to describe how everyone present at such occasions has to take a chance, with the composer most at risk, subject to inaccurate performance, leadership and the audience’s lack of awareness. Not only that, “even though the program says World Premiere, that usually means Last Performance.”

He was once asked to deliver a keynote speech “at the 19th Annual Festival Conference of the American Society of University Composers held at Ohio State University in Columbus on April 4-8. After referring to himself as a ‘buffoon’, he proceeded to puncture any complacency in the room, calling their (and his) work ‘baffling, insipid packages of inconsequential poot’. He told them that popular American musical taste was determined by Debbie, the 13-year-old daughter of “Average, God-fearing American White Folk”, unwitting dupes of ‘the people in the Secret Office Where They Run Everything From’. Frank reiterated his belief that serious contemporary composers were superfluous to American society and should remove themselves from the world before it removed them.”

Zappa, however, continued to write serious classical compositions, such as Time’s Beach, performed by the Aspen Wind Quintet at Alice Tully Hall in New York’s Lincoln Center. The group’s oboist stated, “We felt that Frank Zappa was the quintessential American composer encompassing a wide range of musical experiences, and we felt that he was a really great musician of our time.”

Zappa, eventually went back to touring with a band, embracing the dynamics of imperfect live performance. “The aesthetic goals…have more to do with the growth of the music and a celebration of the good parts of live performance. There are a lot of good things to be said about playing on the stage in terms of unique events that will happen only for that particular audience and if you’ve got a tape running and you’ve captured it, you’ve got a little miracle on your hands…Sometimes the recording quality is not a good as some other version of it, but I want to put as much of the unique stuff in there as possible.”

In 1990 an inoperable tumor was found in Frank’s prostate, and December 6, the Zappa family issued a statement: “Composer Frank Zappa left for his final tour just before 6 pm on Saturday, December 4, 1993, and was buried Sunday, December 5, 1993…”

From the book’s author, “In the relatively short period since his death it’s not possible to quantify Frank Zappa’s achievements or what impact his compositions, of all kinds, will have on the history of music. Throughout his career, he maintained that he wrote music in order to hear what it sounded like. We bought his records to see whether we liked them. That was the contract. The pragmatism of his methods of composition indicated that the results shouldn’t bear the weight of anything other than musical analysis.”

Although, from a moral and Christian standpoint, I have little in common with Frank Zappa; however, a composer who has worked with Symphony Orchestra, modern Classical composition, Rock band, synthesis, sequencing and production of albums, everything Frank said about these subjects, I can personally attest to having the same thoughts. It is inspiring to see that someone else who, 30-40 years ago, actually achieved success in these areas: 1) The importance of music reading (even for the guitar player), 2) Fluidity in multiple styles, 3) Classical disciplines, 4) The use of modern Classical techniques of chromaticism and detailed rhythmic composition, 5) Merging popular styles with Classical disciplines.