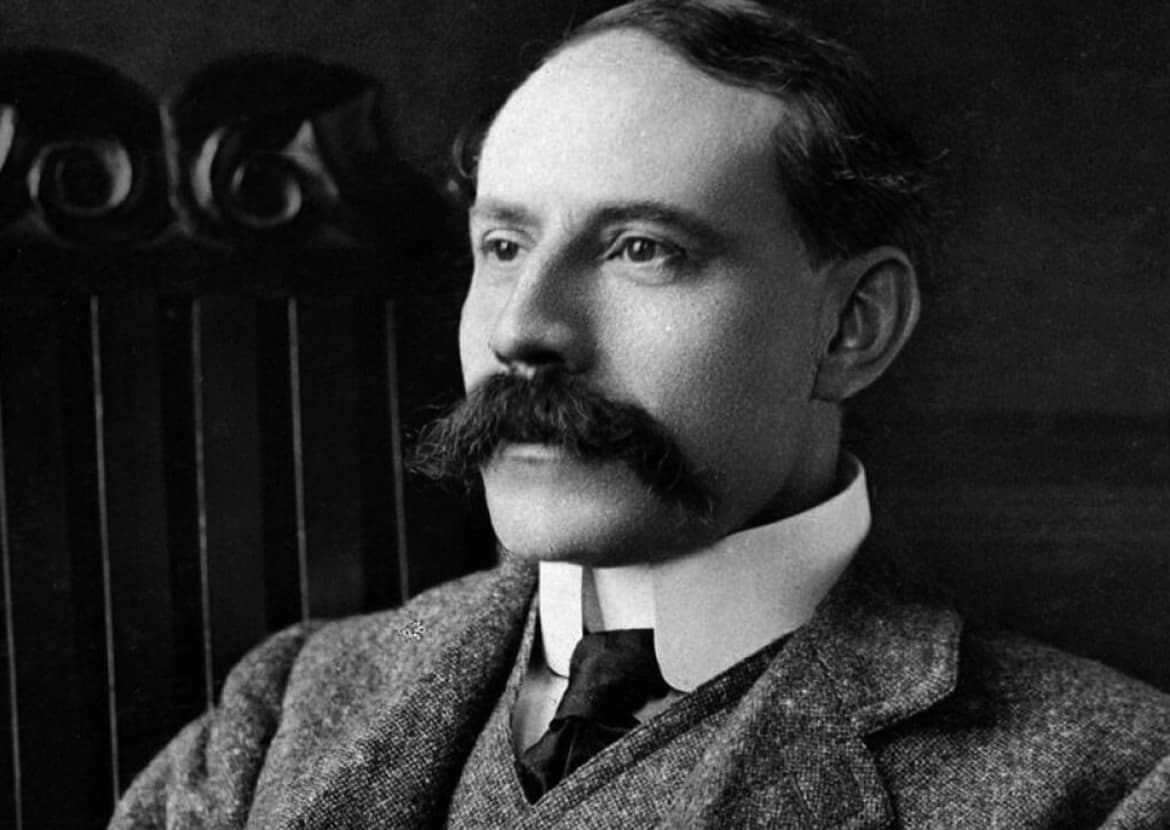

Edward Elgar

The following contains excerpts from the book, Edward Elgar (Michael Messenger).

Elgar was an excellent composer in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. His music is both well-structured and emotionally moving. He was “one of Britain’s greatest composers, but his fame was hard-won. The son of a modest piano-tuner, born in a tiny cottage in rural Worcestershire, brought up as a Roman Catholic in Protestant England and denied the benefits of wealth, university education and formal music training, he overcame those disadvantages to become the most famous British composer of his generation, receiving many of the highest honours that the nation could bestow upon him.” He is most known for his work, the Enigma Variations (1899).

Elgar was born June 2, 1857. He had a life-long enthusiasm for books and reading on a wide variety of topics. “When he left school at fifteen he was desperately anxious to take up music as a career, but the resources of a local music retailer and piano tuner made this impossible and young Edward was sent to work in the office of a local solicitor.”

In his own words, “When I resolved to become a musician and found that the exigencies of life would prevent me from getting any tuition, the only thing to do was to teach myself. I read everything, played everything, and heard everything that I possibly could…I am self-taught in the matter of harmony, counterpoint, form, and, in short, the whole ‘mystery’ of music.” It is this kind of passion that we encourage in the students of our music school in Odessa, Texas.

He played violin and acted as accompanist for the Worcester Glee Club, also writing some music for them. “In 1877 he was appointed leader of the newly formed Worcester Amateur Instrumental Society, and he made a few weekly trips to London, where he had violin lessons from Adolphe Pollitzer.”

He began conducting the Worcester Instrumental Society in 1882. He continued to play and compose, writing some liturgical pieces for St. George’s Church, where he succeeded his father as organist in 1885. He continued teaching, even though he didn’t’ like it. Upon marrying, he and his wife Alice moved to London, however he was unsuccessful at making a living there and returned to the countryside of Malvern. The Malvern Hills provided much inspiration for some of his early works. It was here that he wrote the Enigma Variations, which famously provides a caricature of his friends and associates at that time in each movement, without giving their names, hence, the enigma.

“The Variations were an immediate success when they were performed in London in 1899 and, more than any other single work, helped to bring Elgar’s music to the attention of a wider audience, but the composer still taught locally and remained heavily involved in the local music scene.”

In 1900 Cambridge University awarded Elgar with an honorary doctorate of music. “This must have afforded Elgar some amusement as well as satisfaction, bearing in mind his thinly veiled hostility towards what he felt was an academically biased musical establishment – though the Elgar finances were still such that he initially hesitated to accept the degree and his academic robes were bought only with the aid of a collection amongst his friends.”

“Further honors were to follow…partly in recognition of his growing significance.” After Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, he wrote an Ode for the Coronation of Edward VII in 1902. For its finale Elgar adapted part of the Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1 that he had written during the previous year, and which included a tune that the composer himself prophesied would ‘knock ‘em flat’; the result was Land of Hope and Glory, the one tune everyone associates with Elgar, a stalwart of the last night of the Proms, and calculated to link the composer irrevocably with the image of the Empire.” Students who are trained in our music school in Odessa, Texas bring recognition to our area through their skillfulness and craft.

In 1905, “the University of Birmingham offered Elgar the newly endowed Peyton Chair of Music, a position that he accepted with some reluctance. His initial lecture, ‘A Future for English Music’, proved highly controversial when Elgar, never the most tactful of men, voiced forthright criticism of English music composed during the previous quarter-century, and neither was his second lecture, delivered late in 1905 on ‘English Composers’, calculated to appease the musical establishment of the time, however much posterity may have endorsed his views. Further lectures continued to provide controversy, although it was not until 1908 that he finally resigned the Chair.”

Meanwhile, “his conducting commitments with the London Symphony Orchestra and in the United States (apparently to raise money) left him little time to compose.”

1907, at the age of 51, he wrote his first Symphony. “The celebrated Hans Richter, to whom the symphony was eventually dedicated, paid several visits to Hereford to discuss details, and Richter it was who conducted the Halle Orchestra at the first performance in December 1908. London heard it four days later, again with Richter conducting a piece that he described as ‘the greatest symphony of modern times’, and the public seemed to concur.”

He then wrote his famous Violin Concerto, whom Fritz Kreisler premiered in 1910, as Elgar himself conducted, “confirming Elgar as the pre-eminent composer of the day. Even with all the honors that were bestowed upon him, “it is clear that Elgar’s basic insecurity remained.” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to understand the value of their talents so that they can remain secure in their value as artists.

After writing his 2nd Symphony, Elgar himself conducting, the audience’s response was muted at its first performance. “The composer may have been disappointed, but the critics’ reaction was not unfavourable, although it was to be some years before the true quality of the symphony was widely appreciated.”

“His journeys to London from Malvern and then Hereford had become increasingly frequent as his reputation grew; his publishers were in London, he had been appointed permanent conductor to the London Symphony Orchestra, and it did provide opportunity for the Elgars to socialize. With friends and many of those involved professionally in the business of making music Elgar was amusing, boisterous and generous, and they saw a very different side from the sometimes prickly and irritable composer and conductor experienced by those with whom he felt ill at ease and whom he thought less than professional in their approach to music.”

“In 1914 he was taken…to the recording studios of the Gramophone Company (later His Master’s Voice) and there met Fred Gaisberg…who constantly prompted and encouraged Elgar to record his own music. With his abiding interest in scientific matters and recognizing the enormous educational potential of the gramophone, the composer can have needed little encouragement, despite the primitive recording techniques of the period, and he became the first major composer to commit to record his interpretation of his own works. He made his first record later in 1914, conducting a small orchestra in his own Carissima, a new piece that had received its first performance earlier in the year.” Sometimes, the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas will have to be willing to humbly lead smaller musical situations and learn to grow and ‘bloom where they are planted.’

By his own admission, Elgar wrote, “I am still at heart the dream child who used to be found in the reeds by Severn side with a sheet of paper trying to fix the sounds & longing for something very great.”

“He found London inimical to composition and the inspiration that, by contrast, he derived from the power and the peace of the countryside…It is little wonder that Elgar became more and more depressed, seeing little hope for the future, though a brief holiday did again spark the muse and Elgar resumed work on something he had considered some years earlier: a symphonic poem on the subject of Falstaff.”

In 1917, he had a burst of creative energy and wrote his famed Cello Concerto “with its haunting suggestion of a world lost, and three towering works of the chamber music repertoire: a violin sonata, a piano quintet and a string quartet. All of them contain passages of great lyricism, but equally all are imbued with touches of either the macabre or an innate pessimism, and it is difficult not to believe that they are coloured by the war and the effect it had had upon the composer.” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to find inspiration in their surroundings, no matter how difficult.

In 1920, his wife Alice passed away. “Edward was distraught. His letter to friends are an outpouring of grief and reveal the depth of his feelings at the loss of the one person who had supported, encouraged and sustained him through three decades, and without whom, one may safely say, he would not have become the important figure that he did.”

“There is no doubt that, despite a number of abiding friendships, Elgar was now a very lonely man, and out of sympathy with the times, both social and musical – and though he did help a number of younger composers, notably Arthur Bliss and Arnold Bax, his relationship with them was already unpredictable.”

“From 1926 until shortly before his death Elgar was closely involved with HVM (His Master’s Voice) in preserving for posterity his interpretation of many of his own creations. These included the Cello Concerto (with Beatrice Harrison as the soloist) and the Violin Concerto; the latter, recorded as late as 1932, has become one of the most celebrated of those recordings because of the collaboration between the seventy-five year old composer and the fifteen year old prodigy Yehudi Menuhin.” The students in our music school in Odessa, Texas study these recordings.

“His choral music had become a staple part of the Three Choirs Festival, held in the cathedral cities of Worcester, Hereford and Gloucester in turn, and the elderly composer was a regular visitor to the Festival” where he became friends with George Bernard Shaw. “Shaw had been an admirer of Elgar’s music for some years, even going so far in 1920 as to write publicly that he thought it bore ‘the stigma of immortality’, and the two played duets together at a private function during the Festival.”

He also established a friendly relationship with Vaughan Williams at this time. He wrote to his friend Ernest Newman, “interest in our art is now very slight or perhaps, I should say, dead.”

George Bernard Shaw encouraged him to write his 3rd Symphony, but there were only fragments of ideas upon his death in 1934. In 1997 Anthony Payne completed his realism of the Symphony.”

Edward Elgar was gifted as a composer, and even with the uncertainty this occupation brings, he kept being drawn to create. He tended towards negativity and depression, but overcame these times through his writing, much of which contains truly beautiful passages of lyricism and deeply meaningful harmonies. His stoic British exterior seems to have belied his inner passions. Elgar’s music will be remembered well into the future, much of which has become common fabric to our current culture, even now, a century later.