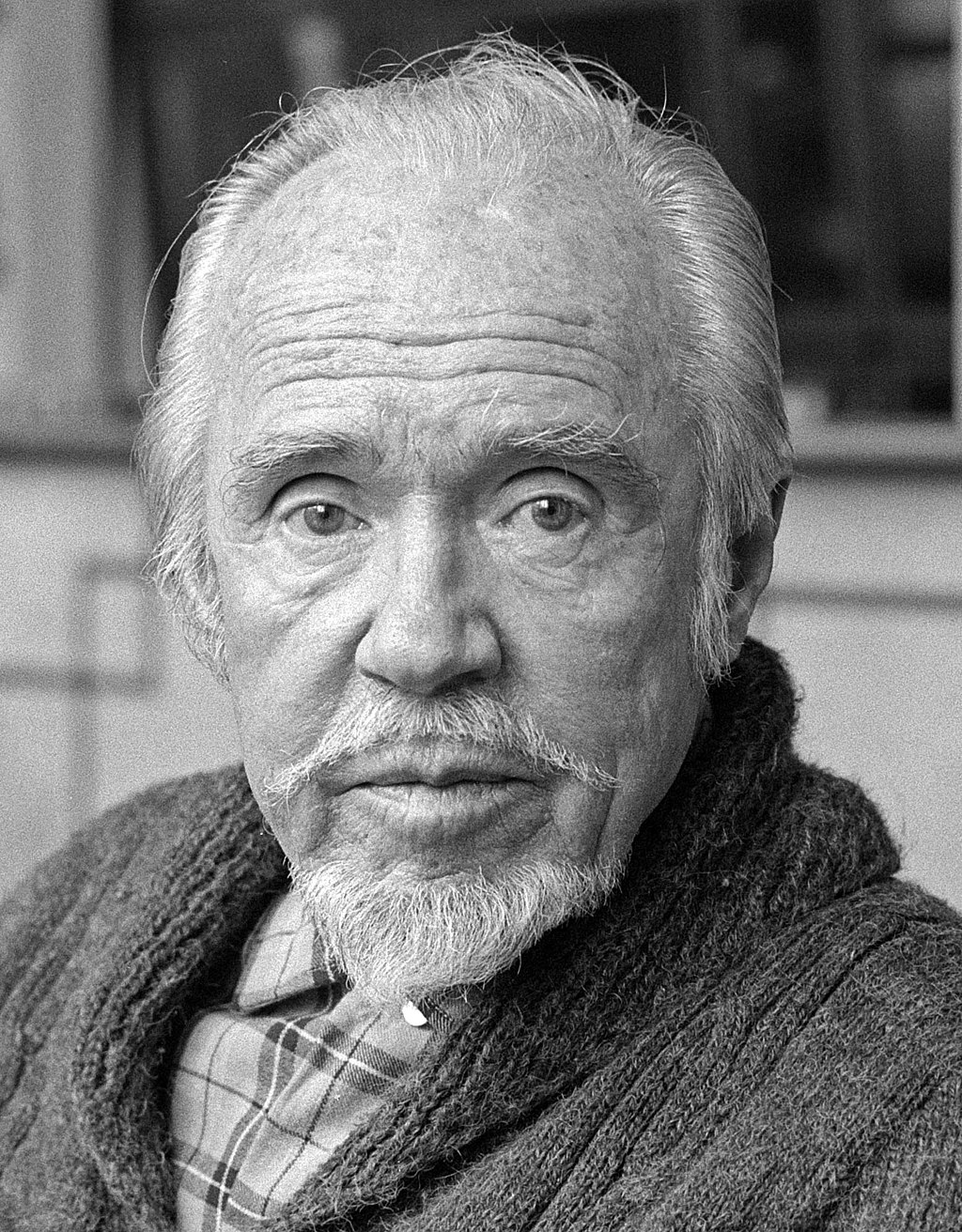

Conlon Nancarrow

The following contains excerpts from the book, The Music of Conlon Nancarrow (Kyle Gann).

In my succession of book-studies, there has been a ‘trail of crumbs,’ bringing me ever-closer to the very edge of contemporary thought in the development and evolution of music. Much of what the contemporary American listener hears through their media device is foundationally built on theory and formulae at least a hundred years old, if not older. But the pioneers of the development of these ideas came early, decades before they became mainstream. They were all avant garde Classical composers who set trends eventually ending up in pop-culture’s Hip-hip, Rap, EDM, the modern synthesizer, and the groundbreaking software Ableton Live. Composers who established the framework for these contemporary manifestations did so at great personal cost. Their names are not well-known to the general public. John Cage, Milton Babbitt, Karlheinz Stockhausen are the originators of the sounds we now enjoy in pop-culture. They made their greatest mark in the middle part of the 20th Century.

Since then, however, there have been other developments by another set of innovators whose work has yet to filter down to the general public. Conlon Nancarrow is one of these voices. His work, although much of it was done in the middle of the 20th century as well, was built on the theoretical writings of Henry Cowell, in his book “New Musical Resources” (1930). Nancarrow took some of the ideas in this book, and in nearly complete artistic isolation for decades, he became a prophetic example, revealing ways of approaching music, that today’s Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) have yet to completely assimilate. We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas how to use such technology in their artistic pursuits.

Nancarrow forecast a time in which computers would create music before anyone knew what a computer was, or how it could be used to create the vast majority of what contemporary listeners hear. Nanacarrow built the majority of his compositions on a Player Piano. This was the only way he could get the mathematic relationships of ratios exactly performed. He was ahead of his time, even compared to his contemporary avant garde compatriots.

“His name must be placed next to those of Ockeghem, Josquin, Bach, Haydn, Webern, and Babbitt as composers who redefined in a technical sense what the act of musical composition can be…he can be counted with Ives, Ruggles, Cowell, Cage, Partch, Harrison, Feldman, Oliveros, Ashley, and Young as one of those outrageously original, challenging minds with which the brief history of American music already seems overly blessed.

“Henry Cowell (1897-1965), an early ethnomusicologist and the twentieth century’s first great theorist of rhythm, invented a new rhythmic notation in an aesthetically revolutionary treatise titled New Musical Resources, published in 1930 though written some dozen years earlier. He was interested in superimposing rhythms derived from equal divisions of a common beat: for example, dividing a whole note into five, six, and seven equal parts, and playing the different beats all at once. This exercise would effectively layer three tempos simultaneously, in ratios of 5:6:7. Addressing the problem of execution, he wrote,

An argument against the development of more diversified rhythms might be their difficulty of performance…Some of the rhythms developed through the present acoustical investigation could not be played by any living performer; but these highly engrossing rhythmical complexes could easily be cut on a player-piano roll. This would give a real reason for writing music specially for player-piano, such as music written for it at present does not seem to have.

“Cowell’s idea was prophetic, but for once in his life, he left an experiment untried. That task fell to another composer: Conlon Nancarrow from Texarkana, Arkansas.

“Nancarrow read New Musical Resources in 1939 in New York, as he was preparing to leave for Mexico City to avoid harassment by the American government…Cowell’s words fused with a childhood memory- Nancarrow had grown up with a player piano in the home…self-exiled in Mexico City far from the musical mainstream, (he) took a step few other composers would or could take: he learned to produce his music independently of performers. In 1948, he bought a player piano and embarked on an amazing series of now more than fifty Studies for Player Piano, exploring more aspects of rhythmic superimposition and tempo clash than any other composer had dreamed of doing. We teach concepts from New Musical Resources to the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas.

“In 1981, after finding his recordings in a Paris record store, seminal Hungarian avant-garde composer György Ligeti wrote of Nancarrow, “This music is the greatest discovery since Webern and Ives…something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, perfectly constructed, but at the same time emotional…for me it’s the best music of any composer living today.”

“Although most of Nancarrow’s works are very brief (only seven of the Studies run over seven minutes), they do not sound brief, largely because of their sheer speed…Study No. 36, for example, is under five minutes, but its score is fifty-two pages black with ink. Consequently, the music demands unusually intense listening…Nancarrow’s complete works could be heard in seven hours, but within half that time the listener would be as exhausted as though he had consumed Mahler’s ten symphonies in a gulp.

“With the arguable exception of Study No. 49, there is not a piece in Nancarrow’s mature output that does not contain some new idea or twist he had never tried before.

- A pitch row split into discreet segments (Study No. 1)

- A pitch row using internal repetitions of a pitch cell (No. 4)

- A texture built up from motives that repeat nonsynchronously, i.e., out of phase (also involving every note on the piano without duplication (No. 5)

- An isorhythm (repeating rhythmic series) altered by systematic changes of tempo (No. 6)

- Different isothythms played at once (No. 7)

- A piece divided simultaneously into equal-length sections by texture changes, and into a different number of equal sections by melodic structure (No. 11)

- Polyphonic use of isorhythm in which the color (pitch row) and talea (rhythmic row) are associated differently in each contrapuntal line (N. 20)

- A canon in which the voices gradually reverse roles (No. 21)

- A palindromic canon (No. 22)

- A correspondence between tempo and register (Nos. 23, 37)

- Rhythmic canon in which the canonic voices have wildly disparate textures (No. 25)

- Use of a 12-tone row as harmonic determinant for triadic music (No. 25)

- Accelerating isorhythmic canon (No. 25)

- A steady beat as a perceptual yardstick for changing tempos (Nos. 27, 28)

- A “scale” of tempos proportional to a pitch scale (Nos. 28, 37)

- Interrupted (and resumed) acceleration (No. 29)

- A tempo canon whose voices theoretically converge outside the canon’s time frame (No. 31)

- Isomorphic transformation of a duration pattern to simulate a tempo canon (No. 33, Two Canons for Ursula)

- Tempo changes within layered tempo contrasts (No. 34)

- An entire movement played at the same time with itself at a different speed (N. 40)

- 21 An isorhythm accelerated by subtracting from the individual durations (N. 42)

- Aleatory tempo canon (N. 44)

- 23 Use of Fibonacci durations to create the same rhythmic motive at different tempos (No. 45)

- Irrational, unnotatable isorhythm (Nos. 45, 46, 47 – originally one work)

- Structural acceleration within a tempo canon (No. 48)

- Tempo canon in which voices are timed to converge not all at the same time (String Quartet #3)

We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to immerse themselves in the above examples of modern music, to understand this new language of macro-polyrhythms and new rhythmic structure.

“The rhythmic theory of Cowell’s book was fueled by the insight that pitch intervals and cross-rhythms are manifestations of the same phenomenon, differentiated only by speed. That is, the higher pitch in a purely-tuned interval of a perfect fifth vibrates at a rate one and a half times that of the lower pitch, illustrating a ratio of 3:2. A triplet rhythm over a duple accompaniment, then- three against two- is simply the transfer of the ‘perfect fifth’ idea from the sphere of pitch to that of rhythm.

“The chronological progression of Nancarrow’s tempo ratios creeps up the harmonic series. The group of seven canonic studies, Nos. 13 through 19, use the ratios related to the major or minor triad: expressed as pitch, 3:4 gives the perfect fourth, 4:5 the major third, 3:5 the major sixth, and 12:15:20 as first-inversion minor triad, i.e., G B E. The 5:6:7:8 ratio of Study No. 32 is analogous to an E G Bb seventh chord, the 17:18:19:20 of No. 36 to a cluster, C# D D# E. The 24:25 and 60:61 ratios of Studies Nos. 43 and 48, respectively closely spaced harmonics in the higher octaves. Study N. 33 uses the irrational √2:2 ratio of the equal-tempered tritone; Nos. 5 and 50 use the 5:7 ratio that is the smallest integral approximation of a triton. And in Studies Nos. 40 and 41 Nancarrow went beyond algebraic square roots to the transcendental numbers e and π, whose pitch analogue is irreducible dissonance. In the more recent Study No. 49 Nancarrow has returned to the 4:5:6 ratio of the root-position major triad.

“Beginning with Study No. 24 and continuing with increasing freedom through his most recent studies, he has preserved the energetic, unpredictable feel of additive rhythms within the context of a tempo system related to the pitch relationships of the harmonic series. Inspired by Stravinski, challenged by Cowell, he is the only composer who completely integrated eh microrhythms of one with the macrorhythms of the other, the only one to solve, rather than bypass, the Schoenberg/Stravinski rhythmic dilemma. Nancarrow achieved this feat, of course, at a price few composers would have been willing to pay: he sacrificed the possibility of performance by humans. These concepts are fundamentally breakthroughs in musical composition, and we encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to appreciate how profoundly altering they are to the history of music creation.

Humorously, “The speed on Nancarrow’s pianos is continuously adjustable, from stopped to quite fast, and he has often changed his mind about how fast the studies should run. To the man who insisted on the absolute precision of relative tempos in his music, absolute tempo is an intuitively relative matter.

“In addition, as Nancarrow has often noted, as the roll winds around the take-up spindle of his player pianos, the thickness of the column increases and causes a slight speed-up in the music. Philosophically, he sees this acceleration as a natural phenomenon that occurs unconsciously in most musical performance, and points to long African drumming performances as a parallel example.

Regarding Nancarrow’s working method (which I am most interested in, to see if there are any correlations that can be drawn to computer sequencing) the author writes the following:

“Once he progressed beyond tempos that could easily fit within a small convergence period, such as 3:4:5, Nancarrow needed a working method that would free him from placing barlines to connect voices every few beats. His solution was to make templates, long strips of poster paper on which a tempo is marked off. Over the years, Nancarrow has collected templates for dozens of tempo relationships the way just-intonationist composer Lou Harrison has collected them for indicating the string lengths of tunings on a monochord. Clearly harking back to Cowell’s theories, Nancarrow identifies each template by a pitch name relating it to a basic “C” tempo; the templates he used for Study No. 42, for example, are marked in the score Bb E D D G Bb D to indicate tempos corresponding to ratios of 7:10:9:8:12:14:18.

“After he uses the templates to mark off tempos on manuscript paper, he sketches out the piece. From this sketch he draws a more detailed punching score, with beat numbers, dynamic markings, and every indicator he needs to punch the roll. This punching score is often a more accurate guide to what actually happens in the piece than the final score. From the punching score he transposes the notes to a piano roll, first marking off the tempos across the top edge of the roll…The process is…heavily time-consuming, however, requiring several months to punch one of the more complex studies.

(This is exactly how sequencing programs are laid out today, probably initiated by Nancarrow’s practices.) We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas how to use sequencer programs.

“No other composer save Nancarrow has ever had the monumental task of drawing every note in his scores in exact rhythmic proportion to all the others. From 1960 to 1965 he quit composing and labored at scoring the first thirty studies, realizing that the musical world was unlikely to take him seriously unless he put his work in a form that lent itself to analysis. The pinpoint accuracy of those scores, in terms not only of pitch but of placing notes precisely within a fluid temporal continuum, is an achievement no other composer has ever had to duplicate.

“The measure of his achievement is that music so complicated in description sounds so vivid and direct. The music invites participation by the brain because it first made such intuitive sense to the ear.”

Nancarrow was born October 27, 1912. He played trumpet, attended the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan, and enjoyed the jazz music of Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, and Earl Hines. “He began composing…around age fifteen, and became determined to go into music. His father, however…wanted him to study engineering.

“In 1934-35, Nancarrow studied privately in Boston, with Roger Sessions, Walter Piston, and Nicolas Slonimsky…In Boston Nancarrow began working for the Works Projects Administration, which employed so many composers through the Depression…He switched to writing incidental music for theater.”

Nancarrow played trumpet in a jazz group for a dance tour, bringing him to London, Paris and Germany.

He went to fight in the Spanish Civil War, and in 1937 “returned to Europe…as a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, who fought with Republican Loyalists in Spain against Franco’s fascist government.

‘I was an idealist in those days, and I thought that if Hitler was defeated there, it might avoid the next war, which was obviously coming. Hitler was spreading out, and taking this and that. I through that might stop him. Of course, it didn’t’ stop him, because the democracies prevented it, with their nonintervention. Well, Hitler intervened, so did Mussolini.’

“Like so many farsighted comrades, Nancarrow saw the fight as a chance to help the Soviets stop the Germans…His battalion defeated by Franco in 1939, Nancarrow made a hair’s-breadth escape from Fascist-dominated Spain, crammed with his fellow Lincoln Brigade members in the hold of a freighter leaving Valencia in the midst of Italian submarines.

“Nancarrow learned that some of his Lincoln Brigade friends were being hassled by the U.S. Government for their membership in the Communist Part. After they had been denied passports, Nancarrow applied for one just to see what would happen; he, too, was denied. He quickly determined not to live under a government that looked on him with suspicion. Mexico and Canada were the only countries he could enter without a passport, and, having little curiosity about Canada, he moved in 1940 to Mexico City, where he has lived ever since.

“Nancarrow’s first performance experiences, which took place during these years, were disastrous. In 1940 he wrote a Septet for a concert by the League of Composers in New York. Only two rehearsals were arranged, only four players showed up for each, and only one of these was the same for both rehearsals. Predictably, the performance was a disaster….In 1942 Halffter asked Nancarrow to write a piece for the Monday Evening Concerts he organized in Mexico City: the result was the Trio for clarinet, bassoon, and piano. Rehearsals went badly; the clarinetist refused to play a piece that would, he said, make the audience think he was playing ‘wrong notes’, and ultimately the work was not played.

“Nancarrow’s father had left a trust fund to support his family though the Depression. For fifteen years it was reserved for Conlon’s mother, but in 1947 the sons became eligible for their share directly, and Conlon began receiving enough money to live on. Given his frugal lifestyle, the money continued to provide considerable support into the sixties, largely freeing him to compose with only a minimum of nonmusical work…And in 1947 he used the money to return to New York City to search for a player piano and punching machine.

From 1947 to 1975, Nancarrow was virtually unknown to the world, working systematically on his experimental compositions for the player piano. However, Peter Garland, composer and publisher of the important American music journal Soundings, published some of his works, subsequently some of them were recorded.

“In 1982 Nancarrow was composer-in-residence at the Cabrillo Festival in Aptos, California, where his early instrumental works from the thirties and forties received their world premieres: Dennis Russell Davies conducted the Piece for Small Orchestra No. 1, the Kronos Quartet played the String Quartet No.1…October and November brought a tour of Graz (the ISCM festival, honoring Nancarrow’s seventieth birthday), Innsbruck, Cologne and Paris’s IRCAM.

“June of 1985 brought Nancarrow to the Almeida festival in London where, featured along with Lou Harrison and Virgil Thomson, he spoke publicly about his own music for the first time in his life.

“In April of 1986, Joel Sachs’s and Cheryl Seltzer’s Continuum ensemble played Nancarrow’s non-mechanical music at Lincoln Center, including the Piece for Small Orchestra No. 2. The following month he was featured at the Pacific Ring Festival at the University of California at San Diego.

“The year 1988 also brought major commissions and a return to writing for live performers. The first commission was from England’s extraordinary Arditti Quartet, for whom Nancarrow wrote his String Quartet N. 3.

In 1989, “one of the year’s most significant events was a visit by Trimpin, a brilliant German musician/engineer who has invented machines for playing many musical instruments via computer. For the sake of preserving Nancarrow’s piano rolls, Trimpin invented a machine to transcribe them into MIDI-compatible computer information. He copied all of Nancarrow’s piano rolls, most of which had existed as unique copies, into computer files, greatly reducing the music’s vulnerability to physical disaster, and opening up the possibility of computerized performance elsewhere. We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas uses and applications of MIDI.

“In 1990 New England Conservatory presented Nancarrow with an honorary doctorate. And in October of that year, the University of Mexico City presented a two-day celebration of Nancarrow’s music, organized by his composer friend Julio Estrada, Nancarrow’s first major honor in Mexico.

Quite healthy throughout his life, he died in 1997 at age 85.

What is remarkable to me about Nancarrow’s story is how devoted he was to his craft, moving into areas no one else had ventured, and he immersed himself in his work without accolades for about three decades before anyone noticed. He was obviously passionate about his work, and the love for it sustained him through the years of obscurity and the painstaking time it took to complete one short piece after another.

Interestingly, I was in New York at the time Joel Sachs performed one of his works mentioned above. Joel Sachs was one of my music history teachers at Juilliard.

I will be spending more time studying, culling through Nancarrow’s works for insight. His ideas are closely aligned with my own studies of integrating frequency and rhythm in a single system.