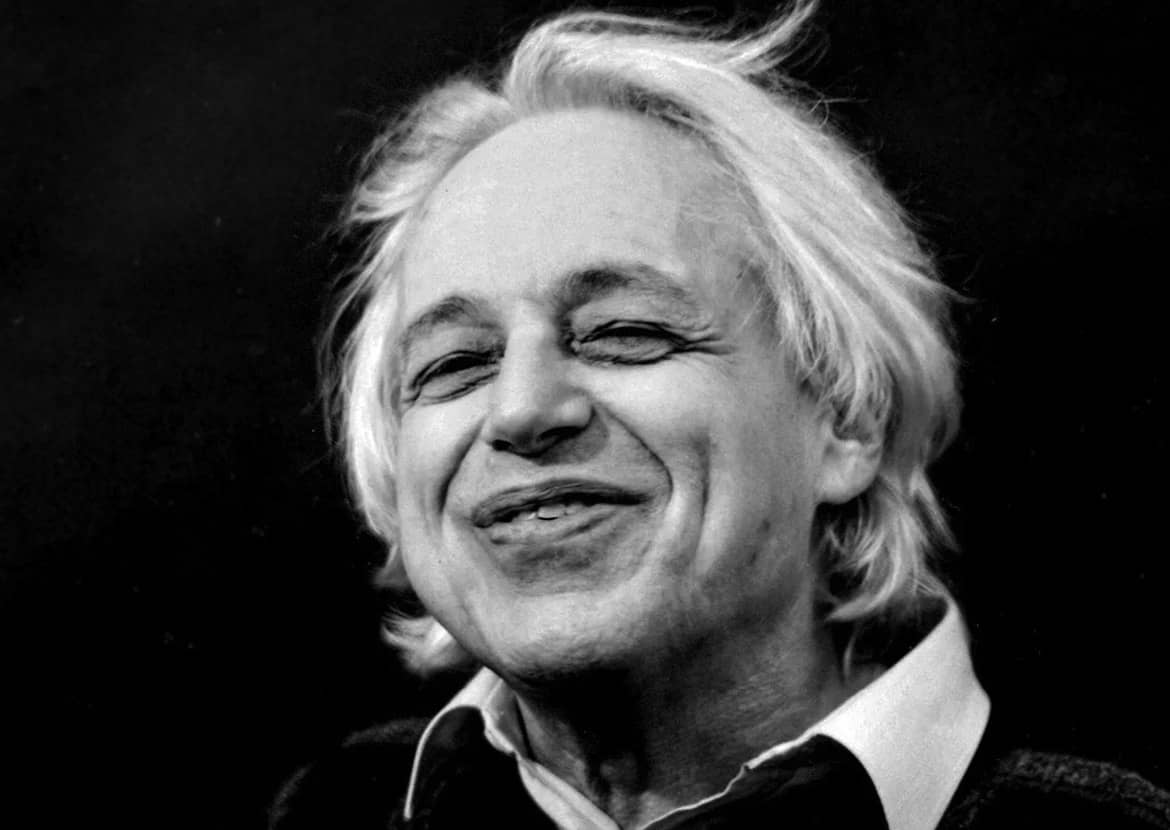

György Ligeti

György Ligeti was one of the most important composers of the 20th century, living into the 21st century (May 28, 1923-June 12, 2006). He was born in Transylvania, Romania, lived in communist Hungary, and became an Austrian citizen in 1956. He was a professor of composition at the Hamburg Hochschule until 1989 and lived in Vienna until his death.

This book is a series of essays written by friends, colleagues, former students and musicologists. “It contains not only reflections on Ligeti as student, teacher and friend but also new insights into how he wrote his music, its structure and its meaning, and the way he received inspiration from a wide range of musical and extra-musical concepts.”

Ligeti “had not only once, but several times over the course of his life, introduced new ways of composing and thinking about music. As early as the late 1950s he developed a technique of dense polyphony, his ‘micropoyphony’, which showed that there were other paths a composer could take to stay clear of both the Scylla of total serialism and the Charybdis of indeterminacy…(and) his many experiments with complex polythythmic textures. Moreover, his fascination with new and unorthodox tuning systems led to the unique sound world of his instrumental works of the 1980s and 90s. We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas about microtonal comoposition.

Richard Taruskin wrote, “We have lots of new music, God knows, that reduces listeners to their cerebral cortex and, in opposition to that, lots…that reduces them to their autonomic nervous system…György Ligeti… and only a few others, [have] seen the need to treat…listeners as fully conscious, fully sentient human beings.”

“Ligeti taught us how to listen, to his music as well as to the music of others. In the 20th century all composers of art music have had to navigate their own way between ‘avant-garde’ music which many see as a purely intellectual exercise and those musical styles blamed of sustaining the modern-day version of Hanslick’s ‘pathological listening’. Indeed, this is certainly one of the 20th century’s crucial challenges to any composer of art music as combining both extremes in order to generate a new musical language has eluded most of them.” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas the value of critical listening.

“Ligeti was not only a prolific composer but also an equally captivating lecturer and interview partner.” He was a devoted student of Sándor Varess in Budapest in the late 1940s and “was influenced not only by Hungarian music and by his teachers, but also by other aspects of Hungarian culture.”

“An influence which formed Ligeti’s outlook on life and determined his artistic choices like no other was his experience as a victim of violence, oppression and tyranny. In his youth he was a member of the Hungarian minority in Romania and during the 1950s he endured the Stalinist communist regime. But it was the murder of his father, brother and several other members of his family in the concentration camps, which shaped his feelings about life and death…ambiguity and irony are both key concepts in the composer’s attempts to deal with the catastrophe which was forced on him at a very young age.”

“Always curious, Ligeti never ceased to learn and was always affected by developments not only in music but also in literature, culture or science. Two of the most important influences during his later years were chaos theory, more specifically fractal geometry, and the music of Sub-Saharan Africa.”

“Simha Arom, also a survivor of the Holocaust, introduced Ligeti to African polyrhythmic music, a discovery which was to be crucial to his work in the 1980s.”

“He was often dissatisfied with his own ideas, but would eventually find a way forward- a process which could take months or years before it bore fruit. Steinitz’s analysis also reveals how much Ligeti could be influenced by the music of other composers or musical cultures; there are well-known references (such as the one to Beethoven’s sonata ‘Les Adieux’ in the Horn Trio) but also unexpected links to composers such as Monteverdi and Janacek.”

Ligeti always sought to balance “the relationship between technical proficiency and aesthetic quality.” This is a crucial concept for success that we teach in our music school in Odessa, Texas.

“It is well known that Stanley Kubrick made use of some of Ligeti’s micropolyphonic works in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and in so doing introduced the composer to a broader public. Kubrick later used Ligeti’s music in two other films, most famously in his last, Eyes Wide Shut.”

(from Transformational Ostinati in György Ligeti’s Sonatas from Colo Cello and Solo Viola, Benjamin Dwyer)

Ligeti had “a regard for Hungarian and Romanian folk elements, a more than passing tribute to Bela Bartok, and a lyricism that marks both Ligeti’s early and late periods…Ligeti felt that a bowed stringed instrument represented the most natural medium for music of such affiliations: itinerant gypsy violin music.”

He would use repetition in a unique way. “Ligeti’s use of a repeating ‘ground’…the repetition of melodic phrases… the reiteration of rhythmic structures…or even entire segments…indeed renders the term ‘ostinato’ an apt choice…As variation and alteration are generated through these reiterations, the most apposite term to describe these mutational processes would be transformational ostinato.”

One of the most important compositional aspects of the Hungarian culture Ligeti used in his works was the Hora lunga (lit. ‘long song’) “Ligeti’s appropriation of the hora lunga ingenuously reconnected him to both his immediate homeland and to the spiritual father of Romanian and Hungarian music, Bela Bartok. Sometime around 1912 Bartok first came across the hora lunga in the territories of Maramures and Satu-Mare – geographical, historical and ethno-cultural regions in northern Transylvania. Such was its significance that Bartok later admitted that his encounter with the hora lunga was the most important development of his musical career. Subsequent research has revealed similar music found as far west as Albania and Algeria, and as far east as Tibet, western China, and Cambodia. Ligeti himself highlighted the ‘striking similarity’ of the hora lunga ‘to the Cante jondo in Andalucia and…folk music in Ragastan’.

Ligeti used the ‘long melody’ in ‘transformational ostinati’ by making small changes to the melody as it progressed throughout the composition. We teach this kind of thematic development in our music school in Odessa, Texas.

“Microtonality has always been an important feature of Ligeti’s work. Rather than employing it in an arbitrary manner in Hora lunga, he utilizes the natural microtonal discrepancies offered by the harmonic series, and in so doing parallels certain developments in the spectral music of Tristan Murail, Horatiu Radulescu and Gerald Grisey.”

In his sonata for solo viola, “While utilizing the altered third and fourth degrees of the imaginary F series, Ligeti also occasionally resorts to their well-tempered pitch versions…The inclusion of these notes results in two slightly different pitch-classes that play against each other. This use of alternative scale patterns further parallels another common trait of the hora lunga genus: the third and fourth degrees of its scale fluctuate between their exact, slightly flat and slightly sharp pitch version.”

“Numerous processes Ligeti employs in this music from the 1970s onwards emerge out of his familiarity with 14th-century polyphony…From 1980 the mechanical ‘studies’ of Conlon Nancarrow (1912-97) also exercise a significant influence. In 1966, Ligeti turned to Guillaume de Machaut (1300-77) in preparation for Lux aeterna.”

He was also influenced by performances of jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli, as he introduced ‘quirky’ jazz elements into some of his music. It is important for students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to expose themselves to a variety of musical styles.

In an interview with Ligeti, he was quoted as saying, “But don’t consider that I take a model whatever it is, biological or otherwise…theory interests me but not for a direct application. Somewhere underneath, very deeply, there’s a common place in our spirit where the beauty of mathematics and the beauty of music meet. But they don’t’ meet on the level of algorithm or making music by calculation. It’s much lower, much deeper- or much higher, you could say.”

“The balancing of relations between indigenous music and art music, parallels Ligeti’s relationship between his dependence on compositional mechanisms and ready-made systems on the one hand, and his intuitive application of them in his music on the other…However, of cardinal interest are the various intuitive processes through which he erodes the very regulatory mechanisms upon which he depends.”

(from À qui homage? Genesis of the Piano Concerto and the Horn Trio, Richard Steinitz)

“The rapidity of stylistic change in the 20th century left composers particularly vulnerable to self-questioning…Ligeti, too, after the premier of his opera Le Grand Macabre in 1978, struggled with deep uncertainty…He had reached a point of profound ‘compositional crisis’. But it was not, as he later explained, only ‘a personal crisis’, rather ‘a crisis of the whole generation to which I belong’.

“During the early 1980s Ligeti was absorbed in new interests, ranging from medieval counterpoint to the music of Central Africa, from Nancarrow’s studies for mechanical piano to molecular biology and computer-generated fractals. These ‘discoveries’ would feed into this music, but how was far from clear. Ligeti’s only major work completed in the seven years after the opera was the Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano…the Trio owes much to Ligeti’s habit of playing chamber music with students of the Hamburg Hochschule für Musick und Theater, a practice dating from soon after his appointment as professor of composition in 1973.”

As to his creative process, Ligeti’s “approach suggests a combination of the mathematical and

sculptural – primarily abstract, although never without dramatic and emotive import. Like many composers, Ligeti worked best within the discipline of self-imposed limits.”

One such preliminary group of sketches was found in a folder containing matrices and mathematical calculations on scraps of card and paper. Most are in fractions and look as if they are serially ordered. Some project durations into realms of astronomical fantasy: in one case 3/2, 9/4, 27/8, 81/16, 243/32, continuing in 12 steps to 531441/4096! By the time Ligeti began the Piano Concerto he had left such unrealistic game-playing far behind.”

In the seven year period of time he was searching, “most of the techniques he had used during the previous 20 years he considered to be exhausted. Tired of clusters and micro-polyphony, disenchanted with an avant-garde ‘that has become academic’ and a Darmstadt ‘transformed into political discussions about progressivity’, the problem was how (in Ligeti’s own words) ‘not to go on composing in the old avant-garde manner that had become a cliché, but also not to decline into a return to earlier styles. I’ve been trying deliberately in these last years to find an answer for myself- a music that doesn’t mean regurgitating the past, including the avant-garde past.’”

“He needed ‘a third way: being myself, without paying heed either to categorization or to fashionable gadgetry’.”

“Few of Ligeti’s contemporaries shared this sense of crisis. During the early 1980s Boulez, Nono and Stockhausen built on what they had achieve to create works of spacious summation: Répons, Prometeo, Licht…For Ligeti, always wary of repeating himself, this was not an option…Unlike some composers, “Ligeti never ring-fenced his aesthetic position by closing his mind to other ways. If his openness and receptivity to ideas and criticism temporarily undermined his confidence, as a means of enrichment and renewal they were rare and invaluable strengths.”

“Ligeti’s determination to quit the avant-garde on the one hand and shun neo-romanticism and minimalism on the other was unshakeable. But what was the alternative? The search for a solution exposed an older reflex- the Bartókian language of Ligeti’s youth…But to be over-influenced by Bartók certainly would not do.”

Even though Ligeti was not inclined to use serialism, “the dominant technique of the mid-century had become an ingrained instinct, and Ligeti’s continued use of 12-note material in subsequent sketches suggests that it was not easily eradicated.” We teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas the techniques of serialism.

“Early in 1980 Ligeti had learnt of the existence of the émigré American composer Conlon Nancarrow, living obscurely in Mexico City, and in the autumn he came across two recordings of Nancarrow’s studies for player piano. Their impact Ligeti described…‘This music is the greatest discovery since Webern and Ives…something great and important for all music history. His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, perfectly constructed, but at the same time emotional…for me it’s the best music of any composer living today.’”

“Could Nancarrow’s combination of breath-taking speed, rhythmic intricacy and unrelated metres be replicated by a human pianist? Ligeti pondered the challenge.”

He answered the question in his Piano Concerto. In this work, Ligeti finally emerged with a style he forged that was uniquely his own. He began using a combination of “independent metres and multi-tonal harmony.”

“The key to the breakthrough was not only polymetric. Polymetre, after all, had been an occasional component of Ligeti’s earlier music…True, the actual first movement is more ingeniously polymetric than anything Ligeti had composed before. But crucially it is supported by something else: the layers are also differentiated harmonically.

“The long gestation of the Concerto had another outcome, for it was also a process of spring-cleaning during which Ligeti discarded techniques no longer useful (clusters, micropolyphony, serialism) and established those which were (polymetre, passacaglia, alternative temperaments, melody)…Above all, it was the partnership between polymetre and Ligeti’s unique brand of multi-tonality that emphatically secured the ground for the achievements of his final years. He was too inclusive a composer wholly to jettison the past. But the renewal was dazzling, securing for Ligeti’s late works an exceptionally wide following amongst the general public.”

(from Rules and Regulation: Lessons from Ligeti’s Compositional Sketches, Jonathan W. Bernard)

“The 20th century saw a great fragmentation of compositional practice; to be sure, the widespread dissemination of dodecaphony and serialism during the 1950s and 60s did indicate a consensus of a kind, but our lengthening perspective on that era shows that it was a consensus of relatively brief duration, and one of limited scope at that. Far more numerous than the ‘committed’ serialists were composers who never subscribed to such methods, or who at most showed only a tentative interest in them – and, as time has gone on, this group has taken on much greater importance than any observer might have predicted even half a century ago.”

Ligeti’s preparation, prior to composing his scores was unique. He made a number of non-musical sketches to begin the process. “Ligeti’s sketches fall into five basic types, any or all of which may be found among the sketches for a particular piece.”

Jottings

“Sketches of this first type involve no musical notation, or even substitute musical notation, of any kind, being strictly prose descriptions of what Ligeti envisions a piece in its early stages…Section by section descriptions are reordered; some are crossed out, others inserted; projected timings, as mentioned, are often revised, sometimes several times over.

Drawings

Drawings, the second category of sketches, are Ligeti’s projections, as visualizations, of how the music is to ‘go’. Often they take on the general aspect of pitch-time graphs, with pitch displayed from low to high on the vertical axis, time elapsing from left to right on the horizontal. These drawings vary greatly in degree of precision, and also of scale: sometimes an entire movement or work is outlined, sometimes only a short section.

“‘In general,’ Ligeti has said, ‘my works abound in images, visual associations, associations of colours, optical effects and forms’; he has admitted to being ‘inclined to synaesthetic perception’. Even more revealing is a comment he made on one occasion about his compositional process; that after first imagining a new work from beginning to end (‘ten times, perhaps 100 times’), ‘the next step is always to have a drawing – no notes. I am never writing directly scores [sic]. They are very similar to what is called graphic notation,’ which he then noted that he had carried directly over to the form of the published score.”

Charts

“In this, the third type of sketch, individual pitches are specified but are usually not displayed in staff notation. Instead, Ligeti uses German pitch names, arranged in vertical stacks. Like the drawing, charts emphasize construction in pitch space; in fact, charts occasionally emerge quite explicitly as realizations of drawings.”

He believed that “although the notation of a score should be as precise as possible, the performance of the music need be only as near to exact as the players or singers can manage – and that the little discrepancies that arise from this effort are not only tolerable but actually part of the composer’s desired effect.”

Tables

“The table is a kind of running account of pitches, rhythms, or durations as they are used in the compositional process – almost as though Ligeti were keeping statistics on his own usages…these categories, pitch or rhythm.

Musical Notation

The fifth type of sketch, finally, encompasses work in conventional musical notation, and can be divided further into two subtypes. First, there are sketches that consist either of pitches in staff notation with no rhythm or duration indicated, or of rhythms with no assigned pitches – the latter much more common after 1980. Rhythmic sketches differ from the rhythmic charts shown earlier in that their contents correspond to specifically worked-out passages or sections of pieces, as opposed to general or generic metric/rhythmic situations. As for pitches in staff notation, there are two basic varieties of sketch…an initital sonority undergoes gradual metamorphosis, as one pitch at a time is altered…Together with similar usages in sketches of earlier pieces in which such a midpoint is literally marked ‘symm’ or ‘asymm’…The second subtype – comprises sketches in more complete musical notation, with notes actually in rhythm.”

In light of this five-part classification of his sketches, Ligeti might well seem at first to be a composer to whom words and pictures mattered almost as much as music. But while it is true that both the verbal and the visual played important roles in his creative process, and in his creative life in general, Ligeti was actually quite traditional in the meticulous way in which he worked out the sound of his pieces….Ligeti’s notation is essentially a direct and accurate representation of a specifically envisioned sonic realization. It may be that the jottings and drawings had a kind of catalytic role to play, and thereafter served as contextual guides, helping him keep the larger dimensions and intentions of his piece in mind as he worked out the details of the score.”

Ligeti created ‘rules’ for himself in many different ways, changing even within the movements of a single composition. He states, ‘‘‘Thus are the rules different for every movement; however, the principle of strict regulation is always fundamentally the same.’”

Having said that, it still remains “that Ligeti finds his particular compositional voice along that sometimes rather hazy boundary between freedom and stricture: freedom on the one hand to make up his own rules, the obligation on the other to obey their constraints…the overall tendency to regulate by principle rather than precept. The idea of keeping things more or less even, which comes out in his self-direction to keep the 12 tones in steady circulation without binding them to rows as such, is one example of a not-so-rigid approach to control that is nonetheless very effective; his methods of guaranteeing that all possibilities of combination will be exhausted…Although the method or methods in use will change from piece to piece, or even from section to section (and sometimes radically at that), it is this approach to regulation (as Ligeti said himself) that can be counted on.”

György Ligeti was one of the most influential composers in the modern era. His willingness to step out into ‘unknown’ territories separates him from most of his contemporaries. At the same time, he had his aesthetic grounding in the traditional classical repertoire, as he regularly played piano in ensembles with music students at the conservatory. They played Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, etc.

Ligeti’s stretching into alternative tunings and polyrhythms points the way toward the synchronization of the two subjects only now possible with today’s technologies. His fascination with Conlon Nancarrow’s work for player piano is significant to today’s sequencing capabilities with the digital audio workstations (DAWs) we have at our fingertips.

With all the available technology we have, it surprises me how far behind most creators are in their aesthetic and perceptual development. Nancarrow and Ligeti are easily a century ahead of their time in comparison to most users of these technological tools. I can’t help but wonder what Ligeti would have done if he had had access and experience with current technologies.

The technologies we enjoy in today’s pop music all has roots in the bold experimentation found in the modern classical era. John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Conlon Nancarrow, and Phillip Glass laid the groundwork for the synthesizer, DJ looping (which became Ableton software), and the DAW (digital audio workstation). It remains to be seen how the experimentation Ligeti introduced of microtonality and polymeters will affect tomorrow’s pop culture. He was well ahead of his time.