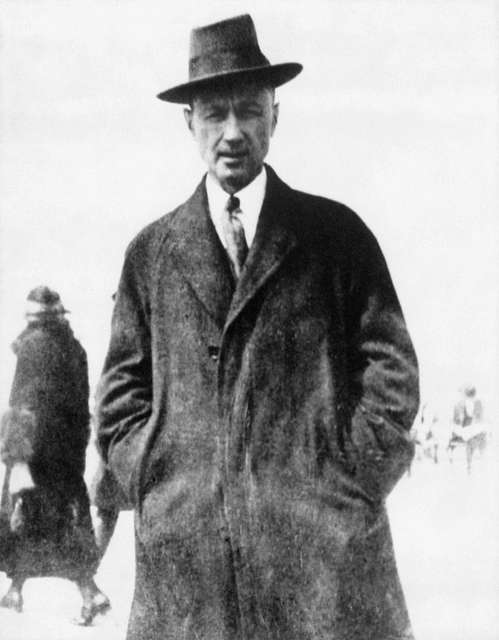

Charles Ives

The following contains excerpts from the book, The Life of Charles Ives (Stewart Feder).

Charles Ives was considered one of the “American Five” composers concerned with innovation in the early part of the 20th century, who became an inspiration to younger composers of generations to come. His music was built solidly on traditional foundations which his father, a fine musician, gave him as a young man. His creativity and distinct Americana sentimentality were embedded in a highly unique and avant-garde approach.

His life was one of polarities. He deeply loved and romanticized traditional America, particularly in the mid-to-late 1800s, and though his music was based on and inspired by this era, it was nonetheless highly modernistic. Now, even a hundred years later, most contemporary audiences would still find it ‘too modern’ to appreciate. Although he loved composing, he was also a very successful insurance salesman in New York, which gave him the financial solidity to pursue his musical ambitions without starving. In fact, he became a leader in the insurance industry at that time. Ultimately, his music paved the way for the distinct American voice future composers would follow. We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to consider this model, as they endeavor to balance their artistic pursuits with making ends meet.

“‘The fabric of existence weaves itself whole,’ said Charles Ives…For Ives, there was no boundary between music and life. Music was life, and life music. He continued, ‘You cannot set an art off in a corner and hope for it to have vitality, reality and substance. There can be nothing exclusive in a substantial art. It comes directly out of the heart of experience of life and thinking about and living life. My work in music helped my business and work in business helped my music.’”

Charles Ives was born in 1874 to a deeply religious family. His father, George, was a very talented musician, who led bands in the Civil war and was distinguished in doing so. He later became Danbury’s leading musician and director for their community, including church. He was well-loved and respected.

Charles wrote, “‘One thing I am certain of is that, if I have done anything good in music, it was, first, because of my father, and second because of my wife…What my father did for me was not only in his teaching, on the technical side etc., but in his influence, his personality, character, and open-mindedness, and his remarkable understanding of the ways of a boy’s heart and mind. He had a remarkable talent for music and for the nature of music and sound, and also a philosophy of music that was unusual.’”

Both Charles and his father possessed perfect pitch. Charles, growing up, was particularly sensitive to sound, particularly those of his childhood experience, hearing the hymns, patriotic tunes, and popular household songs, mostly written in the mid-1800s. We help train students in our music school in Odessa, Texas how to develop pitch memory.

“George was Charlie’s first teacher and although he sensibly passed the boy on to other teachers, he remained his musical mentor and collaborator until Charlie was in college…Ives wrote, ‘Father knew (and filled me up with) Bach and the best of classical music, and the study of harmony and counterpoint etc., and musical history,’ he also filled the boy with unique musical ideas.”

“Play was an important element of the golden age of childhood- inventive play; innocent guilt-free play; joyous play…Play and the playing of music went hand in hand. In musical play George Ives ‘was not against a reasonable amount of ‘boy’s fooling’.”

“Among Ives’s most tender memories of a childhood Utopia were those of his father’s hymn playing, especially at the out-of-doors religious camp meetings. These festivals of prayer, sermon, and hymn-singing had been popular from the time of George’s birth until well after the Civil War and were still held in the countryside surrounding Danbury.”

Charles wrote about his memory of, “‘Father, who led the singing, sometimes with his cornet or his voice, sometimes with both voice and arms, and sometimes in the quieter hymns with a French horn or violin, would always encourage the people to sing their own way…He had a gift of putting something in the music which meant more sometimes than when some people sang the words.’” The value of emotional expression in music cannot be overstated, and we encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to connect with their innermost feelings.

George started the boy on piano and soon introduced the other instruments in which he was most competent – the violin and cornet. Later, perceiving Charlie’s gifts, he saw to it that the best teachers in town were engaged for lessons on piano, later organ…He also drilled his student in sight reading. Ear training was of a special nature, as Ives would later say of some of his own music, ‘half serious, half fun.’ Ives wrote: ‘I couldn’t have been more than ten years old when he would occasionally have us sing, for instance, a tune like The Swanee River in the key of E-flat, but play the accompaniment in the key of C. This was to stretch our ears and strengthen our musical minds.’ But it was fun, too.”

On occasion, George “had his bandsmen stationed in different quarters of the green in order to experience the special spatial quality of sound coming from different directions as he moved about…creating an illusion of indeterminate yet ever-changing space.”

“The hymn tunes already well familiar to Charlie constituted a religious vernacular tradition that the young church organist absorbed. In church, the four-part hymn tunes were performed and improvised upon.” We help students in our music school in Odessa, Texas learn how to improvise as well as read music.

“Humor had always been an aspect of the vernacular trend, and in their individual ways father and son were both humorists.”

In a song Charles later wrote, Things Our Fathers Loved, he penned:

I think there must be a place in the soul

All made of tunes, of tunes of long ago;

I hear the organ on the Main Street corner,

Aunt Sarah humming gospels;

Summer evenings,

The village cornet band playing in the square.

The town’s Red White and Blue, all Red White and Blue

Now! Hear the songs! I know not what are the words

But they sing in my soul of the things our Fathers loved.

The arts, however, “in general were viewed as polar to the masculine, and indeed it was through music in particular that many women could find a place for themselves in the economic world.”

As Ives applied for and was accepted into Yale, he had to distinguish himself among his peers as being ‘manly.’ He did so in many ways, particularly by joining the baseball team.

“The professed mission of Yale under Timothy Dwight was to mold character by ‘a common and all-embracing discipline,’ and to send forth men ‘to engage in altruistic service in a Christian commonwealth.”

At Yale, Ives studied with the distinguished American composer Horatio Parker, and served at Center Church in New Haven as organist during his student days.

As a student, Ives composed music for numerous occasions, some of which were intended to garner favor with his classmates by way of making ‘musical jokes’ or parodies. “Ives composed or performed many musical stunts during his college years. It proved to be a way of currying favor with classmates, while at the same time carrying on the composer’s private, musical experimentation. The two endeavors came together in Ives’s earnest desire for his peers to endorse creative activities which might otherwise be considered effeminate, or worse, crazy. The fun of it all often screened out a serious element but enabled it and made it acceptable. What was serious was musical experimentation and what the effort meant to Ives the person…Ives wrote a middle movement to a Trio for piano, cello, and violin that he was working on that he called ‘TSIAJ,” and acronym for ‘This Scherzo is A Joke.’” However, TSIAJ is no joke, or rather it is and is not at the same time. Multiple serious issues go into its makeup.” It was also at Yale that he completed his First Symphony and began working on his Second.

Upon graduating, he secured a job in New York as organist at the First Presbyterian Church in Bloomfield, New Jersey…The following year he got a better and closer job at New York’s Central Presbyterian Church.”

“Doctor Granville White was George Ives’s second cousin on his mother’s die…Doctor White was a medical examiner for the Mutual Life Insurance Company in New York, and helped Ives get a job in the actuarial department. There he served as clerk, compiling insurance statistics of mortality, calculating risks, and deriving premiums.”

“Quite aside form Ives’s musical world, which became increasingly private, life after Yale was centered on ‘measuring up’…one must now show one’s manliness in the earning of a living and perhaps the establishment of an estate; the achievement of a degree of power and influence; the winning of a desirable and suitable mate; and the ability to comfortably support a family.”

In 1902, when Ives’s work Celestial Country received a New York Times review that was less than complimentary, he decided he would give up music as a career and even resigned his position as church organist at Central Presbyterian Church. “In addition, there was not a single public performance of any of his music during the next fourteen years.”

“What he embraced was at the core of his developing identity as composer which paved the way for his most original works. For Ives retreated all the more into composition in an innovative and experimental style. He composed now in a concentrated manner in evenings and at weekends, still using the beat-up piano in Poverty Flat…Musically isolated, Ives was free to pursue his own ideas unfettered by institutional requirements of the conservative ears of teachers and audiences.”

“With the ‘giving up’ of music of 1902, Ives also began to experiment with genres he had not yet explored in any detail; hence the First and Second Violin Sonatas (1902-8), the First Piano Sonata (1901-9), and the Trio for violin, cello, and piano.”

“If any single work can be said to be Ives’s ‘signature’ piece, it is The Unanswered Question. That Ives called it ‘A Cosmic Sometime Landscape’ connects it to such spiritual landscapes as The Pond…Throughout this period Ives led a second life in which he was also creative…he proved to have the gifts of making go-getters of his agents. In business, a façade of good fellowship of a respectable nature stood in strong contrast to the privacy of his musical life.”

Meanwhile, he wrote his Third Symphony, which was “smaller in both scale and scope, focusing on aspects of everyday Protestant New England religion…seen and heard through the senses of a small boy, remembered not only in tranquility but in maturity and in full command of an original composer’s voice…It was Ives’s Third Symphony that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1947. It remains, in all its simplicity, one of Ives’s fullest and most feelingful statements about one of the several facets of a complex spiritual life.”

But he was very innovative in his business life. “He proved to be skilled in training the agents in salesmanship and had a knack for showing others how to get a foot in the door…The income endowed a way of life that favored musical creativity. Derived from commerce, it served to insulate music from musical commerce. Meanwhile, marriage stabilized Ives…Ives worked visibly at composition evenings and weekends supported by an undemanding and soothing marriage partner…One of his secretaries noted this: ‘At work sometimes, Mr. Ives would be dictating a letter, and all of a sudden, something in the music line would come up in his head, and he’d cut off the letter and go into music. I think that music was on his mind all the time.’” We hope to help students in our music school in Odessa, Texas understand the dynamics of creativity, helping them become aware of creative ideas and capturing them when they come.

“In 1922 Charles Ives privately published three related works that he had been composing and thinking about for a long time. They were the final products of his decade-long creative period from 1908-18 and, in important ways, the fruits of his entire creative lifetime….the Second Piano Sonata…frequently called the Concord Sonata; a set of accompanying essays, the Essays Before a Sonata; and a culminating collection of 114 Songs.”

“He would have them published privately at his own expense and personally send copies to a variety of people, musicians and others. The works would not be copyrighted; they were meant as a gift to the world and, above all, to Ives himself.”

“The Fourth Symphony and the Concord Sonata may also be viewed as Ives’s final complete works.

He began working on what would have been his Fifth Symphony, calling it his Universe Symphony, but never completed it, due to increasing physical and mental health issues.

“In the ‘Epilogue’ to the Essays Before a Sonata, Ives writes, ‘maybe music was not intended to satisfy the curious definiteness of man. Maybe it is better to hope that music may always be a transcendental language in the most extravagant sense.’ Vague as this is, it points to ‘the way things happen.’ Ives in acknowledging the elusiveness of the concept, tried to address it in a discussion of the dualism of ‘manner’ and ‘substance’ in music. Substance is achieved through intuition, while manner is the medium that transforms it into expression. ‘Substance can be expressed in music,’ he asserts, ‘and it is the only valuable thing in it…The substance of a tune comes from somewhere near the soul, and the manner from – God knows where.”

“Ives told his first biographers, the Cowells, that he envisaged a performance of the Universe in which “several different orchestras, with huge conclaves of singing men and women, are to be placed about in valleys, on hillsides and on mountain tops.”

“Ives, at fifty-eight, retired from business.”

In 1926, struggling with bouts of depression and diabetes mellitus, he had neuritis in both arms and auditory problems. With his hands shaking, and the perception that sound was wavering, “He came downstairs one day with tears in his eyes, and said he couldn’t seem to compose anymore – nothing went well, nothing sounded right.”

“By the 1930s Ives had become increasingly irritable and phobic, given to outbursts…A suspiciousness which bordered on paranoia was associated with anxiety and fostered withdrawal. As Ives gained the performances he now craved and increasingly fostered, critics of his music became enemies.”

However, Ives’s generosity to Henry Cowell’s publication New Musical Quarterly fostered a positive relationship between the two and ultimately opened a door with the conductor Nicolas Slonimsky. “In January 1931, Slonimsky premiered the Three Places in New England at New York’s Town Hall. Ives was ebullient….In June, Slonimsky presented the program at a Pan American Association concert in Paris.”

Ives endeavored to foster relationships with younger composers, including Lou Harrison, who helped proof-read and correct parts for a performance of the Second String Quartet.

Through collaborations with Harrison and Cowell, Ives was hopeful that he could complete his Universe.

“In his last years Universe kept Ives alive as he kept its spirit and aspiration…He said, ‘If only I could have done it. It’s all there – the mountains and the fields.’ Asked what he had wanted to do, he replied, ‘the Universe Symphony. If only I could have done it.’”

He died nearing eighty, May of 1954.

In many ways, Ives rose above the demise of the ‘struggling artist’ by becoming successful in business. But at the same time, he seemed to regret not having had the opportunity to complete the amount of creativity he had inside of himself, his time divided between the two disparate parts of his life. He knew his music would not afford him financial success, and that was probably a wise observation. But I think his remorse in having to ‘let go’ of his full creative genius eventually caught up to him emotionally.

Nevertheless, his music did make an historical impact, eventually. His decision to live a dual-life as composer and businessman was probably the right one, regarding the society in which he found himself. Perhaps the real antagonist in this story is the culture’s inability to see and support such genius.

We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to consider the works of this American treasure found in the works of Charles Ives.