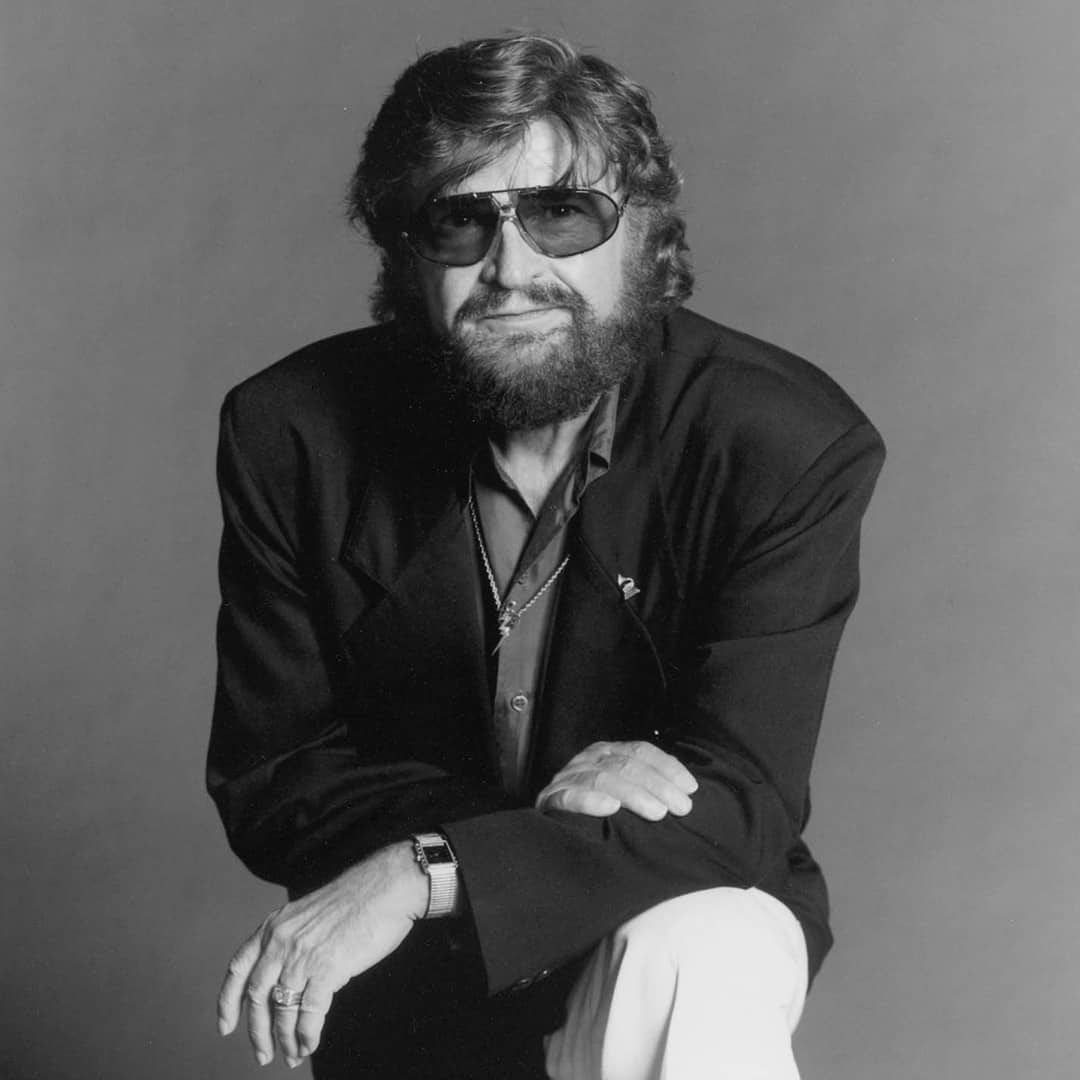

Sam Phillips – Part 01

Sam Phillips was not a musician, per se; however, he became the mentor of artists’ sounds and styles, as their recording engineer at Sun Records. He personally sparked what became a world-wide phenomenon we now know as ‘Rock ‘n Roll’. His initial goal as a radio engineer in Memphis was to give black artists a ‘voice’ for their music, but after a lack of consumer support for this, he began looking for white men with a ‘black’ sound. His first artists were Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, and Ike Turner, then he found (and honed the skills of) young men like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis.

The early beginnings of each of the artists mentioned above was Christianity, particularly Pentecostal and Assembly of God. Growing up, Phillips admired from a distance the difficulties and resilience of the black man, along with the racial prejudices still permeating the culture, and he wanted to provide a place that extended an unbiased platform for their expression. Phillips was a deeply convicted man in certain ways. He always wanted authenticity in the unique expressivity of the common man.

“From this, he took a lesson: value the original, fragile, and rough. That’s the art.” (Holland Cotter on the art of Henri Matisse)

“I didn’t set out to revolutionize the world,’ he said one time. Instead, what he wanted to do was to test the proposition that there was something ‘very profound’ in the lives of ordinary people, black and white, irrespective of social acceptance. ‘I knew the physical separation of the races- but I knew the integration of their souls…when Negro artists in the South who wanted to make a record,’ he declared early on, ‘ just had no place to go.’ It went against all practical considerations, it went against all well-intended advice. He considered himself not a crusader (‘I don’t like crusaders as such’) but an explorer. To Sam, ‘Rock and roll was no accident. Absolutely no accident at all.’” We encourage the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to understand the importance of Rock’s influence on the world.

“He was simply trying to pare things down to their most expressive essence. Michelangelo said: ‘In every block of marble I see a statue as plain as though it stood before me, shaped and perfect in attitude and action. I have only to hew away the rough walls that imprison the lovely apparition to reveal it to the other eyes as mine see it.’ That was what Sam Phillips saw not in marble but in untried, untested, unspoken-for people: an eloquence and a gift that sometimes they did not even know they possessed.”

“Sam was driven by a creative vision that left him with no alternative but to persist in his determination to give voice to those who had no voice. ‘With the belief that I had in this music, in these people,’ he said, ‘I would have been the biggest damn coward on God’s green earth if I had not.’”

“He saw himself as a teacher and a preacher. That was the motivation… ‘to bring out of a person what was in him…to help him express what he believed his message to be.’ To Sam every session was meant to be like ‘the making of ‘Gone with the Wind,’ with all its epic grandeur- but at the same time every session had to be fun, too. If it wasn’t fun, it wasn’t worth doing, he said, and if you weren’t doing something different, of course, then you weren’t doing anything at all. As far as failure went, there could be no such thing in his studio, because in the end, Sam insisted, it was all about individuated self-expression, nothing more, nothing less.”

“‘Perfect imperfection’ was the watchword- both in life and in art- in other words, take the hand you’re dealt and then make something of it…If a telephone went off in the middle of a session, well, you kept that telephone in- just make sure it’s THE BEST-SOUNDING **** TELEPHPONE IN THE WORLD”

“He would return again and again to the same themes over the years, with different details and different emphases, but always with the same underlying message: the inherent nobility not so much of man as of freedom, and the implied responsibility- no, the obligation– for each of us to be as different as our individuated natures allowed us to be. To be different, in Sam’s words, in the extreme.” We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to find their creative uniqueness.

Sam Phillips grew up as a young boy on a farm about ten miles outside Florence, Alabama. “He couldn’t understand why all the little black boys and girls he worked and played with couldn’t go to the same little country school that he did; he registered the unfairness of the way in which people were arbitrarily set apart by the color of their skin, and he though, What if I had been born black? And he admired the way they dealt with adversity- he envied them their power of resilience…he kept his thoughts to himself and listened to the a cappella singing that came from the fields, testament as he saw it, whether sacred or secular, to an invincible human spirit and spirituality.”

“They found a way to worship. You could hear it. You could feel it. You didn’t have to be inside a building, you could participate in a cotton patch, picking four rows at a time, at 110 degrees! I mean, I saw the inequity. But even at five or six years old I found myself caught up in a type of emotional reaction that was, instead of depressing- I mean, these were some of the astutest people I’ve ever known, and they were in [most] cases almost totally overlooked, except as a beast of burden- but even at that age, I recognized that: Hey! The backs of these people aren’t broken, they [can] find it in their souls to live a life that is not going to take the joy of living away.”

Although his family was Methodist, as a youth, he was drawn to participate in a Baptist church in town. “When the Highland Baptist Church dedicated its sprawling new edifice in 1936 and subsequently committed itself to a dynamic youth program under the leadership of Pastor F.L. Hacker, J.W. jumped right in, declaring that he had found his calling, he was going to be a preacher, and persuading his scrawny younger brother that there was an opportunity for the Phillips brothers to make their mark. With his motivating, infectiously upbeat personality, his charismatic presence, and the seeming effortlessness of his soaring oratorical skills, J.W., everyone agreed, was born to preach, and soon he and Sam were holding services in the garage out behind the house on North Royal, packing the modest structure with young people brought together under the banner of their own DeMolay Council, an interfaith Christion you group founded in Kansas City…J.W. held the little congregation spellbound, while Sam enrolled in the church’s BYPU (Baptist Young People’s Union) study course and formed a gospel quartet, in which he sang bass, to back up J.W.’s preaching.”

“It was J.W. who first conceived of the idea of driving to Dallas to hear Dr. Truett preach…for the past forty-two years pastor of the First Baptist Church in Dallas, which under his guidance had become the largest church in the world…There to meet them at the door was a well-dressed man with a big smile on his face who greeted each and every one of the thousands who had come to attend service that day with an outstretched hand. That turned out to be the church’s world-famous music director Robert Coleman, the compiler, Sam knew, of the standard Baptist hymnal, the very one that they employed at Highland Baptist, and what struck Sam even more than the fact of his presence outside the church was his contagious enthusiasm for the job. He made every single soul who turned out that day feel comfortable, far from acting high and mighty, he made every one of them feel as if they belonged there just as much as he did himself.”

Toward the end of his school years, Phillips read the motivational book by Ralston Purina founder William Danforth that influenced him greatly. “Danforth gave the copyright of his little book to the American Youth Foundation, and the Foundation, which he had cofounded a decade earlier, published the book more widely to encapsulate its own stated aims- the physical, mental, moral, and social betterment of American youth. (Its motto was, ‘My own self, At my very best, All the time.’ I Dare You!, however, became a phenomenon in its own right as a result of both its giveaway in schools across the nation and its passionate adoption by businessmen, educators, church leaders, and impressionable youth alike…but its overall message could be boiled down to one central tenet: Dare to be different, dare to be great, dare to take on the challenges that life hands you without flinching…To live, in other words, was to dare. And Sam Phillips, who would cherish the book to the end of his life, as much for what it seemed by its presentation to recognize about him as for its articulated message, was fully determined to take that dare.”

In 1942, Sam met Becky Burns, who would later become his wife. “Becky herself was an intensely religious person who had been brought up Lutheran.”

Sam got into radio, and became the engineer for WREC. He noticed that the station played “All the best of the big bands (the white big bands, Sam was quick to note- there was no Duke Ellington, no Count Basie, ‘not one black person in any of the bands’). When Sam would set up mikes in the studio for live broadcast, he only had six microphones to work with. “He set up differently for every band, and he took a set of lead sheets down to the control room in the basement so he could know when a trumpet or a saxophone or piano solo was coming up and then be able to mix on the fly.” We teach students in our music school in Odessa,Texas the value of proper miking techniques.

Sam became convinced that there was a listening audience “absolutely starved for something new, something different, something fresh. And not just a black audience either…Sam just knew…that there was a new day dawning, that the race music you heard coming out on all the little labels and radio station that were cropping up all over the country, all the records that were flooding the marketplace now…was more and more beginning to resemble the music that had inspired him, the music that he had first heard growing up in the cotton fields of Alabama.”

When Sam would place the microphones at the station, he “sought to restore some of the ‘bottom’ that was so instrumental in propelling them along- each band required something different.”

Marion Keisker Macinnes… ‘was probably the best-known female radio personality in the city…Before long she didn’t want anybody but Sam playing the records. It wasn’t simply because of his engineering skills, Sam soon came to realize… ‘I mean, this is just the truth- she was in love with me. That was it.’” Sam pitched to her the idea he had in his heart to expose black talent, and through her business connections, she made it possible for him to open a recording studio.

“It was slow at first. It took him a while to even get any black people to come it, let alone come in with the idea of making a record.” Eventually, Riley King (age 22) came in, who had also been working in radio. “Sam like him immediately…he saw B.B. as retaining some of that wonderful old Mississippi feel, and, as it turned out, B.B. couldn’t really play in the more modern style anyway. For one thing, he couldn’t always execute the pretty chords that he was aiming for. For another, his timing, which in T-Bone’s case was the rock-solid basis for his blues, was erratic. But most surprising of all, he couldn’t sing and play at the same time. Sam thought at first he was kidding, but B.B. assured him he was not- he had tried, and he simply could not. It had to be, Sam assumed, some kind of mental block.” We hope to inspire the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to take chances and experiment with unique ideas and unique personal relationships. Many times amazing things come about as a result of trying something new.

Sam encountered some persecution from others in the radio industry. “Everybody laughed at me. Of course, they’d try to make it tongue-in-cheek, talking about my recording niggers (and these were some of the greatest friends in the world). They’d say, ‘Well, you smell okay, Sam. I guess you haven’t been hanging around those niggers today.’ It hurt. It hurt deeply.”

It wasn’t too much longer that the song “Rocket 88” was crafted in his studio (themed off the car General Motors had just produced). Ike Turned recorded it, and it became a huge success.

Stepping out into ‘unknown waters’ was not easy. “At the beginning of May it all seemed to catch up with Sam. He was working eighteen to twenty hours a day; he was down to 123, 124 pounds, fifteen pounds less than what he normally carried on his slender five-foot-nine-inch frame; and just like in Decatur he could feel the onset of the panic attacks that he had experienced from time to time ever since he was a boy. At what should have been his moment of greatest triumph he simply ran out of physical and emotion al steam.

“Rocket 88 hit number 1 on the Billboard rhythm and blues charts on June 9 (1951) and stayed there well into July. By the end of August it would sell over one hundred thousand copies.”

“Howlin’ Wolf, born Chester Arthur Burnett in White Station, Mississippi, near Tupelo, in 1910, had an early-morning broadcast every Saturday on KWEM in West Memphis, selling farm implements and dry goods and advertising his appearances in the area…But it was Wolf’s voice that unwaveringly compelled attention.” Wolf became the next superstar launched by Sam Phillips. Sam’s dream to “provide a forum for Negro talent and self-expression, to serve both the black community and the community at large by drawing attention to the rich, generous, and diverse culture that had been so ignored by history and ill served by prejudice” was taking shape, soon under the name Sun Records.

He began to realize his role in the production of great music. “All that was required of him was the quality of ‘transference’ that enabled him to put himself in the place of each person who stood in the front of the microphone. That was how…he was able to give each and every person who came into his studio a sense of self-worth. ‘Put it another way, give them confidence in their ability.’ He knew without a doubt- don’t ask him how he knew, he just knew– ‘that I could discern things that were different.’ That was the one characteristic on which he prided himself most.” We hope to teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas how to discern potentially successful new creative directions.

By 1954, money was tight. “For the first time, there was a strange lack of direction in his thinking. When he opened the studio he knew exactly what he was doing, however much it might go against all the odds…But now, it seemed, he was no longer as certain of his path. Not because the music was any less compelling, or his purpose any less clear. But he had run up against the outer limits of what he felt he could accomplish in this particular way- like the other independent record company owners, he had come to the realization that, no matter how big a hit he had in the r&b field, he was never going to sell more than sixty thousand copies, one hundred thousand at the outside- and for the most part he was going to sell considerably less. And yet he was aware there was an audience out there that was just waiting to be inspired by this music.” We hope to help students in our music school in Odessa, Texas understand their audience and to perceive their taste in musical style and aesthetic.

Many times, there are opportunities all around us for new and creative possibilities just waiting for someone to see the potential and take a risk to develop it.