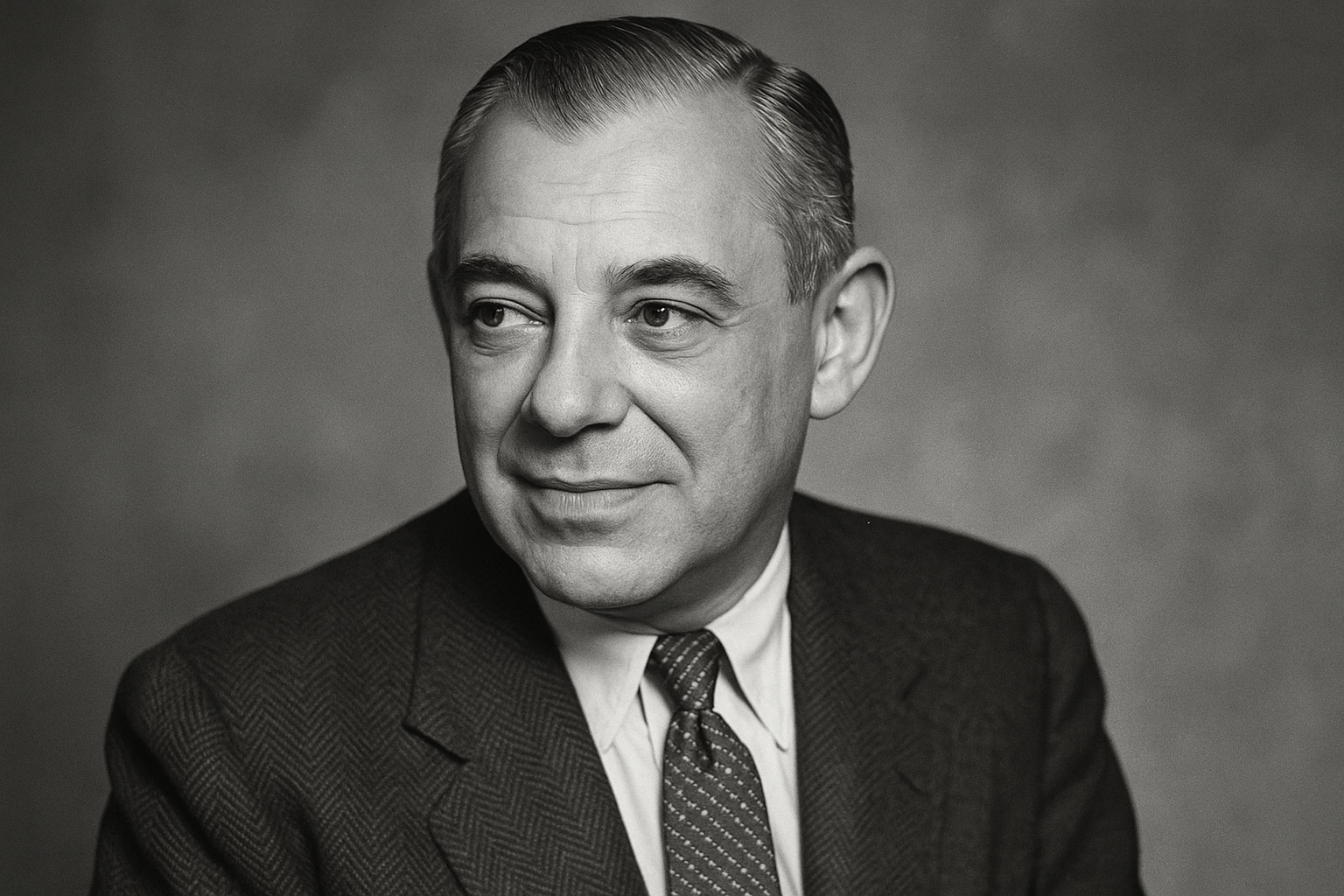

Richard Rodgers – Part 02

This beautifully written (and volumous) biography of Rodgers brings the reader into the feel of New York City’s bustling Broadway through the 20th Century. The career Rodgers had was successful, but always fraught with dilemmas to surmount, all the way to the end of his life. Among his greatest personal attributes were his strong work ethic, his determination to look for what was beautiful in the midst of dark situations, and his commitment to developing his talent in the areas of his specific love of musical theater over a lifetime.

As Rogers and Hammerstein continued to succeed, they transitioned from ‘trying to please’ audiences into striving for artistry. “They would not do today what they did yesterday…That dictum, Hammerstein said confidently, did not include worrying about what the public wanted. ‘We decide on what we want to do and then we hope the public will want it.’” We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to maintain their artistic integrity while at the same time continuing to relate to their audience.

Some of their most successful musicals were: Oklahoma!, Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I, and The Sound of Music. By 1951, “Receptions were being held and awards were showered upon (them). They were becoming the equivalent of national treasures and the subject of numerous radio and television specials. There was an evening of Richard Rodgers of NBC-TV…followed by two one-hour programs on the Ed Sullivan show devoted to his career…a year later, the mayor of New York declared a Rodgers and Hammerstein week. In 1954, a one-and-a-half-hour program featuring the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein was carried on all four networks: NBC-TV, CBS-TV, ABC-TV and Dumont-TV. But to Rogers, the crowning moment came in 1954 when he conducted the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in a program of his own music. It was the fulfillment of a lifetime’s ambition.” We try to help students in our music school in Odessa, Texas see the ‘long game’ of a successful and full career.

“That Rodgers wanted to be recognized as a composer of serious works had become apparent in his speeches and newspaper and magazine articles…he chose…to criticize what he called the arbitrary division between the high and low arts, on the ground that this was hindering the development of a distinctive American music, which would always draw its main strength from folk traditions. His solution was, not surprisingly, the genre of musical theatre, so perfectly suited to reconcile either end of the spectrum, from the crassly commercial to the most esoteric. He would become increasingly impatient with the argument that because his and Hammerstein’s work was so popular, it must therefore be inconsequential…Rodgers also chafed under the criticism that he was a composer of limited range, confined to show tunes. This was hardly fair, since he had written two ballets…demonstrating his ability to compose on a larger scale, and his seven-and-a-half-minute ‘Soliloquy’ for…Carousel was rightly seen as a landmark example of what could be done with an extended form, one that would influence Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, among others. But Rodgers was still dissatisfied. He wanted his name associated with a huge work, something everyone (even music critics) would have to concede was important. His opportunity would come with Victory at Sea.” We encourage students in our music school in Odessa, Texas to continue to stretch their capabilities and expand their world.

Even though Rodgers and Hammerstein were successful, they would not allow themselves to rest on their laurels. “No matter what the notices, they would sit down within a few days to talk about a new show…Their futures had been secure ever since Carousel. But there was nevertheless a necessary dimension to their determination to keep going…This was truer of Rodgers than of Hammerstein once the latter passed the magic age of sixty and began to think of himself as someone who had earned the right to stop and watch the shadows cross the grass. For Rodgers, this was more than the work of a lifetime; it was a lifeline. As he said to Don Fellows, when the subject of success of failure arose, ‘if you lose your momentum you’re dead.’” Always stretching, always growing, never resting on one’s past is an important lesson we endeavor to teach students in our music school in Odessa, Texas.

Hammerstein was tired. In the summer of 1958, he had two surgeries that had left him physically exhausted as he embarked upon Flower Drum Song and The Sound of Music.

“The Sound of Music can be seen as more than a coda, if less than a culmination. Just the same, the era of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical was coming to an end. Two years before, in 1957, West Side Story had ushered in another kind of musical theatre, with its dark meditations on formerly taboo themes that would lead, in due course, to Sondheim’s chilling Sweeney Todd. It was the appearance of ‘boulevard nihilism,’ as John Lahr quipped, full of cynicism, ambivalent emotions, and bitter endings.”

Hammerstein’s health was failing, and in August, 1960, he died. Rodgers was deeply moved at his death, and equally concerned about moving forwards, “No matter how complicated his life had become, even frightening…how could he stop now?…not ready to be turned out to pasture. ‘It’s very easy for an upset man to retire. As you get older you get more scared. But what would I do if I retired? I’m not a golfer. What would I do after a cruise around the world- live on my memories?’”

He began searching for another collaborator, and in 1962, he launched No Strings, having collaborated with Alan Jay Lerner, featuring singer Diahann Carroll.

Rodgers was a generous man, known for his benevolence. “There was a young black singer with a glorious voice at Juilliard, not then married, living in a slum…she was supporting herself as a waitress, and she had no money. He supported her through Juilliard, and paid for her apartment, plus a stipend so she would be well dressed. She went on to the metropolitan Opera. She was Shirley Verrett.”

“For many years Rodgers had been establishing endowments and wards…established a production award (he endowed it with $1 million) to provide for staged and studio readings of new musicals. He established three scholarships at Juilliard, scholarships for professional training at the American Theatre Wing, and gave commissions to composers. (He and Hammerstein commissioned Aaron Copland’s The Tender Land.”

“By 1970, Rodgers had celebrated his fiftieth anniversary on the stage, was a multimillionaire and one of the most famous musical-theatre composers in Broadway history. No other composer had equaled him, not just for longevity but for size of output and for the enduring nature of his songs, so many of which had withstood the test of time and been rediscovered by successive generations…No popular composer had a larger influence on ‘the form, content and tone of the art of musical comedy- an art that many people, with considerable reason, believe to be America’s most characteristic and vital contribution…to music.”

“Like the best in this genre, Rodgers’ songs ‘trade in specific and complex emotions, expressed through a prism of artifice that bends them toward irony and abstraction…distinguished by the predominance of melody over harmony and rhythm…and by, in the best cases, exceptional with and wrenching loneliness.”

“What Rodgers displayed was a gift more to be valued than speed, versatility, dramatic appropriateness, or even a subliminal understanding of the needs of his times: that of the inevitable melody.” We endeavor to help students in our music school in Odessa, Texas appreciate the power of well-crafted music. Richard Rogers’ melodic expression is certainly a pattern to study.

“Rodgers was never able to explain the well-spring of his art…” ‘I’m a commercial theatre kid. I don’t write for posterity,’ “The very idea that inspiration was somehow involved would elicit total scorn.

‘That’s a bad word for what happens to me when I write. What I do is not as fancy as some people may think. It is simply using the medium to express emotion. If my medium happened to be colors, I would be trying to express what I feel in that medium. Mine happen to be notes. It’s a particularly potent medium, maybe because it’s the only purely abstract one. You can make it mean whatever you like. You have a situation in a play, say, where a girl and boy have never met before. They…affect each other- superficially, if they are superficial people, or deeply if they are more emotional, or with certain intellectual overtones if they are intellectual. Your job is to translate this situation and these people into musical terms. This isn’t a question of sitting on the top of a hill and waiting for inspiration to strike. It’s work. People have said, ‘you’re a genius.’ I say, ‘No, it’s my job.’” Another crucial concept we hope to instill in the students in our music school in Odessa, Texas is that of hard work. No amount of inspiration can make up for sheer hard work and practice.

As Rodgers approached his 70th birthday in June 1972, he was looking for another project. His health had been beginning to fail. An avid smoker all his life, he developed cancer in his jaw, and had his voice-box removed. He had had a stroke and a heart-attack, but he continued to work on Rex. His final work, I Remember Mama, opened at the end of May 1979. His daughter said, “I think by the time I Remember Mama closed he was horrendously depressed, but he’d been on a downward slope anyway. Nobody knew what caused his headaches.”

By 1979, he was completely physically dependent on Dorothy. “Richard Rodgers died on December 30, 1979, just three months after his last show closed. The marquees of Broadway theatres went dark for one minute in his memory, just as they had done for Oscar Hammerstein.”

“Late in life, Richard Rodgers wrote, “There is a traditional trick that theatre people have played as long as I can remember. A veteran member of a company will order a gullible newcomer to find the key to the curtain. Naturally, the joke is that there is no such thing. I have been in the theatre over fifty years, and I don’t think anyone would consider me naïve, but all my life I’ve been searching for that key. And I’m still looking…”

The sweetest sounds I’ll ever hear

Are still inside my head.

The kindest words I’ll ever know Are waiting to be said.

The most entrancing sight of all

Is yet for me to see.

And the dearest love in all the world

Is waiting somewhere for me.

Is waiting somewhere, somewhere for me.

-“The Sweetest Sounds,” from No Strings

music and lyrics by Richard Rodgers

Some of the most meaningful musical experiences I have had were created by Rodgers and Hammerstein. Among my favorites: “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning” (from Oklahoma!), “My Favorite Things” and “Climb Every Mountain” (from The Sound of Music). While discovering his ‘human imperfections’ in this book was disappointing, his musical gift still touched my life profoundly.